Table of Contents

- TRADITIONAL GAMES AND EDUCATION TO LEARN TO CREATE BONDS. TO CREATE BONDS TO LEARN

- ABSTRACT

- INTRODUCTION

- TO LEARN TO MAKE CONTACTS WITH OTHER PEOPLE

- TO LEARN HOW TO BE IN RELATION WITH SPACE

- TO LEARN HOW TO BE IN RELATION WITH MATERIAL OBJECTS

- TO LEARN HOW TO BE IN RELATION WITH TIME

- SEARCHING FOR A PEDAGOGY OF MOTOR BEHAVIOUR

- TO PLAY AND TO BE IN RELATION WITH TRADITIONAL GAMES. SOME PARTICULAR EXPERIENCES

- REFERENCES

STUDIES IN PHYSICAL CULTURE AND TOURISM

Vol. 11, No. 1, 2004

PERE LAVEGA

INEFC-Lleida (University of Lleida)

Correspondence should be addressed to: E-mail:

Table of Contents

- ABSTRACT

- INTRODUCTION

- TO LEARN TO MAKE CONTACTS WITH OTHER PEOPLE

- TO LEARN HOW TO BE IN RELATION WITH SPACE

- TO LEARN HOW TO BE IN RELATION WITH MATERIAL OBJECTS

- TO LEARN HOW TO BE IN RELATION WITH TIME

- SEARCHING FOR A PEDAGOGY OF MOTOR BEHAVIOUR

- TO PLAY AND TO BE IN RELATION WITH TRADITIONAL GAMES. SOME PARTICULAR EXPERIENCES

- REFERENCES

Key words: traditional games, education, culture, motor praxiology.

Traditional games are understood as an authentic society in miniature, a laboratory of social and cultural relationships in which the actors, thanks to tradition, learn to create relationships with other people and with their social and cultural environment. In application of these playful activities we should be aware of concept of “internal logic” of a game, which means that the proprieties and the “grammar” of any game order players to solve different types of problems associated with specific ways of being in relation with other people, space, material objects and time. At the same time, the internal logic of a traditional game is impregnated with local cultural conditions (external logic) in which it has been played, showing a genuine playful inheritance, characterized by a singular ensemble of relationships, values, meanings and symbolisms. This paper focuses on understanding and use of both dimensions: internal logic (or text) and external logic (or context), and describes some pedagogical experiences based on these domains.

To play, to learn, to educate, to create bonds… are verbal forms that when combined, they remain active in all aspects of human being.

Among different games invented for a singular occasion, or exercises designed for particular sport training, traditional games have had a special place in their process of shaping human relations and forms of social organization which are worth recognition. Three concepts associated with traditional games should be highlighted in the introduction to the following paper:

1. Oral transmission process

Traditional games are playful activities the rules of which are generally learned by oral transmission. Without being necessarily part of academic knowledge, traditional games – like other cultural manifestations – are learned in an oral way, by way of observation, speaking, listening and especially playing. In the essence of traditional games, we can discover important heritage understood as a cultural knowledge and habits transmitted with the passage of time[ 1].

2. Direct association of traditional games with their social and cultural context

In each locality (village, town, city) traditional games are often accompanied by local features, which provides a close connection with their surroundings. In the same way, in different periods of history traditional games were played using specific appearances, symbols and meanings. For this reason, any contextualized vision of traditional games should consider the two co-ordinates of space (geography) and time (historical period), in which any playful activity acquires its main social and cultural meaning.

3. Traditional games as a social and cultural learning classroom

Within this conceptual framework any traditional game is presented as a kind of micro-society or socio-cultural laboratory, in which actors, thanks to tradition, learn to create bonds.

The contextualized vision of traditional games brings us to the concept of ethno-motoricity formulated by Parlebas (2001) as “the field and nature of motor activities, considered from the point of view of their relation with the culture and social background in which they have been developed” [2].

Thanks to traditional games their protagonists represent in a simple and deep way particular, social and cultural organizations and specific manners in creating bonds in life and its understanding.

Parlebas, the creator of the motor action science or motor praxiology, shows in a very intelligent way using the system theory, that any motor game[ 2] can be perceived as a praxiological system whose components are ordered in a logical way and display operative mechanisms and different properties in each case. Independently of the players’ characteristics, any game has a “grammar” (or a “musical score”), and when this activity is played, different motor actions (“musical notes” played in a motor way) emerge. A game player is like a musician who interprets his “internal laws” or “grammar” by carrying out individualized motor actions (e.g. running, swimming, jumping, kicking a ball, rescuing a partner) and trying to play a perfect tune.

In this theoretical context, the concept of internal logic is an important key to the understanding that in any traditional game the players are invited to participate in a kind of network of internal motor relations, predetermined by a system of obligations and regulations which the rules of the game require. By observing a player who plays different motor games it is easy to see that in each activity his/her motor types of behaviour are different; thus pillow fights, shuttlecock, hoop, cat’s cradles, boules, tug of war and hopscotch possess their own proprieties and internal order.

The relationship with other people is different in pillow fight (in which players wage a fight while straddling a log above a pond. The winner, of course, is supposed to keep his seat on the log) than in cat’s cradle (in which two players cooperate in order to make figures of string woven between their palms).

The relationship with space is quite different in the Chinese game of shuttlecock than in the Chugack Eskimo hoop game. In the former two or more players can play by kicking the shuttlecock between them until one player lets it fall and drops out of the game; in the latter a hoop is pushed along by one player, who also keeps score, as the rival players from two teams took turns throwing long poles through the hoop.

The relationship with objects is different in the well-known English game of quoits than in some French games of boules. In quoits two clay “beds” stand 18 yards apart, each with an iron “hob” in the centre. Each team stands at one bed and players alternately pitch quoits at the opposite bed. In some boules games it is required that the balls be thrown or rolled on the ground toward a certain goal.

Finally, the relationship with time is different in a Korean tug-of-war game and in hopscotch games. In the tug-of-war six members from each team clasp their hands around each other’s waists, and the team captains hold their hands tight. At the count of three, each team tries to pull the opposing players over a dividing line drawn on take ground between them. In hopscotch players act alternatively to toss an object onto the pattern and then hop into, through, and out of the pattern without touching the lines with either feet or hands. The first player who completes the entire pattern wins the game [3].

At the same time, when players decide to play the same game all of them need to be adapted to the same regularities imposed by the rules. For instance, in hide-and-seek games, each player must decide to find a hiding place, consider the possibilities of success and failure, risk to run very quickly and deceive the tag player so they will remain in relation with the opponent (What to do with him?); with the play-ground (Where to hide? How to use the spaces?); and with time (When to run or stop?). All these aspects are distinctive regularities of the game’s internal logic.

When we use the concept of internal logic we should keep in mind that the motor actions performed in any game (e.g. looking for a place to hide, fleeing the hiding place, running behind the adversary if you are the seeker in hide and seek) are the results of the whole of the relationships that any player has with the other protagonists, space, objects and time.

In the case of traditional games their internal logic is impregnated with the culture where they have been played, showing genuine playful inheritance, characterized by a singular ensemble of relationships, learning and symbolisms.

Games are in consonance with the culture to which they belong, especially with regard to the characteristics of the internal logic, which illustrates the values and the subjacent symbolism of that culture: relations of power, function of violence, images of the man and the woman, forms of sociability, contact with the environment… [4]

In a recent study of traditional 17th-century games, Parlebas [5]focused on the games described by Stella in order to reveal features which appear in the playful practices of that time. His posed and meticulous work allows the author to affirm very eloquent conclusions: the games are played mainly by male protagonists; they do not make use of a specific and fixed playground made for this playful purpose; they do not have a formal calendar; they do not have temporal conditions in their internal logic; they do not use any criteria of classification, measurement or accountancy of interventions; they are closely related to the natural and domesticated environment with a number of different playing objects; motor games constitute the most important group of activities (95.5%), more than among the purely cognitive ones. These characteristics confirm an observation that the body dimension prevailed in the 17th century. At the same time the type of interaction in these traditional games reveals that a large majority of socio-motor activities (with motor interaction among players) focus on the exchange and body communication with preponderance of games played by a group of players than by teams. Nevertheless, they did not privilege yet the structure of the duel and the antagonism which would characterize the sport from the 19th century onwards.

Bruegel in the 16th century and Stella in the 17th century showed in their paintings the features of the internal logic of traditional medieval games. These activities “carry the seal of a new social organization which will try to discipline the playful disorder by founding the accounting and the power of the rules. This evolution directed towards an impeccable ordering will culminate in the 20th-century sport, which, in accordance with the values of its context, will increase very much competition, measurement and the spectacle” [6].

Although the internal logic of the games is an excellent mirror to observe the ensemble of relationships and ways of learning that traditional games activate, this vision can be refined if the information provided by the internal logic is completed with data related to the external logic or socio-cultural conditions of the context of these activities [7].

The internal logic of a traditional game can be also completed by using the concept of “external logic” related to new symbolic, unusual, or specific meanings. The internal logic pays attention to the study of internal properties determined by the rules of a game; whereas the external logic concentrates on those local conditions, values and meanings related to the game players. In this way, if we complete the internal vision of a game with the external logic data we are able to offer a great ensemble of information by understanding traditional games as a socio-cultural system [8].

This pertains especially to relationships with other participants (according to age, sex, or social class; e.g. hoop games were important to the American Indians primarily as a way of training young boys in marksmanship, and some centuries later as a popular pastime of young people; knucklebones were played by Greek soldiers, women from aristocratic families and school children); with zones (meaning specific places for playing games: streets, squares, taverns; e.g. an English throwing game known as shove ha’penny was primarily a tavern game and some centuries later it became a pub game); with materials (related to process of hand-making and personalizing objects for the purpose of the game; for instance, yo-yo is made of wood, cat’s cradle of woven string; knucklebones are mutton leg bones called astragals, and all of them are usually painted and decorated); and with temporal localization (concerning the moment of practice: festivity, celebration of the end to a season – spring, summer, autumn, winter; meteorological-cycle year; for example in some cultures tug-of-war was a ritual that dramatized forces of nature affecting the livelihood of people; Canadian Eskimo communities split into two teams for the autumn tug-of-war that foretells the winter weather).

Traditional games are an authentic society in miniature, a laboratory of interpersonal relations. As this condition is very important to justify the treasure and the educational potentiality of traditional games, it deserves a thorough discussion.

1. From internal logic

The social nature of traditional games is identified in the network or ensemble of manners interacting in a motor way with others.[ 3] When somebody is playing a game, the rules, the pacts and the symbols find life by leading the protagonists to have a global image of the network of social relations that they develop. Who are my partners? Who are my opponents? Do I have just one opponent or must I fight against more people? With whom can I make an alliance? These questions are examples that generate different relations and symbolic representations in their actors.

The following criteria are shown in order to understand the educational potentiality of so vast and varied motor relationships that traditional games offer.[ 4]

1.1. Presence or absence of partners and opponents

Four groups of traditional games are considered by applying the criterion of motor interaction with the other players:

a) Psychomotor games. These activities offer a relation of indifference between the protagonists; no player can help or be prejudiced against the other participants, considering there is not a motor interaction among them. It is a situation related to two jumpers; between two quoits or disc throwers; between two skittle players; or between two darts players.

b) Sociomotor games of cooperation. The motor interaction of cooperation can be accomplished by a body contact (run holding the partner’s hand, carry a partner, dance body to body); or through sharing an object (pass a ball, hold the rope in skipping games).

c) Sociomotor games of opposition. To be opposed means to interact in a motor way against one or more opponents. The relations of opposition will directly affect the motor actions of other players. These actions can be carried out thanks to the body contact (knock the adversary down in fight games), through the use of an object (strike the adversary in games of confrontation with instruments; throw the ball far away from the opponent in traditional ball games), or generating a negative change of roles (capture an adversary in the game of hide and seek; eliminate a rival in tag games).

d) Sociomotor games of cooperation and opposition. In these games the players can be helped by their partners and can be opposed by their adversaries in a number of different options explained to them beforehand. The cooperation can also appear through a positive change of roles (for example, saving a partner who is captured in the game of double flag); at the same level, a negative change of the roles is another way of being opposed (for example, capturing an adversary in the games of chain tags). Team tug-of-war, team ball games or team pétanque are good examples of this category.

1.2. Characteristics of the motor communication network

Each game offers a specific motor communication network by which players will have an excellent way to establish different motor relationships. We suggest the use of the basic ideas associated with the concept of this “universal model” called the motor communication network created by Parlebas (2001), in order to identify all the different ways of motor interaction in traditional games.

a) Traditional games with an exclusive or ambivalent network

By applying this universal principle, we can affirm that a traditional game has an exclusive motor communication network when its players cannot be partners and adversaries at the same time. In these games each player always knows who his/her partners are and who his/her adversaries are. The exclusive network is present in psychomotor games (hopscotch, throw- and-catch games, knucklebones, tossing the weight, or skittles), in games of cooperation (jump rope, dance and rhythmical games), in games of opposition (wrestling, ball games, hop races) and in some games of cooperation and opposition (team ball games, team chasing games, team tug-of-war, pickaback relay racing).

On the other hand there are games with an ambivalent network in which any player can play constantly as a partner and/or as an opponent. These games are only games of cooperation-opposition and they offer interesting paradoxical or contradictory situations. The four corners (note that the middle player is opposed by all the others, while all players who are in the four corners can be helped with by or opposed to themselves), and for instance the game of the sit-down ball (where any player with the ball can capture or help the other protagonists according to his/her intention) are examples that belong to this category.

b) Traditional games with a stable or unstable network

At the same time, the motor communication network can be exclusive or ambivalent, and stable or unstable.

The stable network appears in games where the relationships of competition or solidarity do not vary during the match. From the beginning till the end of the match each player has the same partners and the same adversaries. In this category we can find some examples among the psychomotor traditional games (skittles, bar throw, weight lifting), the sociomotor traditional games of opposition (wrestling, individual duels, or ball games) and some sociomotor games of cooperation and opposition (team ball games, the flag).

The unstable network is associated with those activities where the protagonists vary the relations of partnership or opposition during the match, i.e. the partners that I have at the beginning of the game can become my adversaries during the match, and my adversaries at the beginning of the game can become my partners before the game is over. Some tag games featuring the structure of “one against all” are examples of this category; in some of these games one player runs towards the others and when he or she catches one opponent, both of them change their roles. The last tag becomes a player who wants to escape. Sometimes in the chase games a central player chases and attempts to tag or capture the other players.

There are also games with the structure “one against all – all against one”, such as the chain tag. Here, the first one or two players are opponents of the others, and they run holding each other by their hands; when they capture an opponent he/she becomes a new partner who joins them holding their hands to capture the others. This sequence is repeated until the game is over and all players are captured. Another example is the hunter ball (a chain tag using a ball). Finally, we can also identify some paradoxical games like the four corners and the sit down ball.

1.3. The social structure of the motor interaction

To conclude with this vast sample of possible forms to make contacts with the others, we need to consider the different categories of social structures of traditional games according to their motor communication network [9].

a) Psychomotor games. They do not feature motor communication among players. For example: yoyo, jumps, throws, skittles, the metal disc, hopscotch, kites.

b) Cooperation games. Players cooperate with one another, e.g. “corros” (rhythmical circle games), jump rope, dancing games. Children often chant traditional rhymes to the beat of the rope on the ground.

c) One against all. A central player tries to capture the other participants, e.g. numerous tag games.

d) Individual duels. Confrontation between two players. Two groups of games can be distinguished:

Symmetrical Duels: games of combat, wrestling with hammer, with the hands, for example, a game of shuttlecock in which a small feathered ball or disc is kicked from player to player.

Dissymmetrical Duels: e.g. striking hands.

e) Team duels. Confrontation between two teams. There are also two options:

Symmetrical duels: bars, the captive ball, team ball games.

Dissymmetrical duels: the flag or the riding ball, the chambot, the fisherman’s net, the ball with the bear, the rod, the bear, and all the games involving two teams in a competitive relationship in which one team chase the other.

f) All against all. All the players oppose one another. For example, tearing off tails, sets of balls, the named ball.

g) One against all – all against one. In some games the players join hands with the “He” when they are caught and help him catch the other players until all the players are caught. For example, the chain, the ball with the hunter, the sparrow hawk and pigeons.

h) All against all by teams. Multiple teams of partnership oppose one another, for example, pickaback bouts (confrontation between N-teams of players; in each team a player carries his partner, while trying to unbalance and knock down their adversaries).

i) Ambivalent games (paradoxical). All the players can be partners or opponents with no clear criteria. For example, the four corners, the sit down ball, three fields.

2. From external logic

In accordance with the external vision (outside conditions form the rules of games) it is important to know which processes of transmission have been followed by traditional games and who have been their main actors. It is necessary to consider that, for example, hopscotch is a traditional game with clear religious connotations which in ancestral times was played by adults; today it is played by young girls.

The rural society usually differentiates between the roles and the statutes of people, and traditional games are a good mirror of that reality. Often the force, violence and confrontation by body contact appear in male games; while the partnership, stylized skills and songs are often present in the female ones. For example, knucklebones for girls is a psychomotor game that consists of performing various “figures” – throws and catches of the bones in a chosen sequence. The situation is quite different in knucklebones for boys: it is a game of opposition where players can strike and punish the opponents that make a mistake when they throw the bones.

In three recent studies, Lavega et al. [10], carried out in the localities of the Valley of Corb River (the area of Urgell Lleida, Spain), the analysis of the catalogued traditional games indicates that female games are in 65% activities of cooperation, while boys prefer games of confrontation (only 21% of boys’ games of cooperation). In addition, when girls play to antagonistic games, they usually do with the structures of “all against all and one against all” (games with with changes of motor relations – unstable network), whereas boys prefer to play through structures of “individual duels” and “all against all” (without changes of motor relations – stable network).

We have noted that it is girls rather than boys who play the games of ritual and rhythm and indoor games. Cooperative and rhythmic games are predominantly girls’ games (rope-jumping, hand-clapping games, ball-bouncing games). On the other hand, skill games are, by and large, mostly boys’ games.

Undoubtedly, the relationships, the symbols and the learning orientation are different between the two sexes, because in the rural environment the social status is different in each case. Girls display a tendency towards cooperation-types of behaviour associated, for example, with domestic tasks; while boys make contacts with each other through antagonistic games. This circumstance could be linked to the necessity to learn to be adapted to challenge of the adversities and the discomfort of the agricultural work (trying to combat the changing weather, limitation of economic resources).

1. From internal logic

Traditional games offer a vast range of different forms to be in relation with space. In the next paragraphs some of these options which justify their pedagogical dimension are shown.

1.1. Games played in a stable space

In these situations the playing space is usually arranged, prepared and controlled in order to avoid unpredicted motor actions.

In the case of traditional games these types of situations are not very common because in general they do not require specific conditioning of the surfaces. We may consider some situations from school playgrounds or examples of traditional games that have become traditional sports and need to be played in standardized spaces.

The influence of sport understood as spectacle on physical education has brought about an obsession to use standardized spaces in which the responses are very controlled and expected. This tendency offers the students to be educated in situations in which the automatism or reproduction of motor stereotypes precedes cognitive answers, motor intelligence or decision-making, in order to clarify the uncertainty [11].

1.2. Games played in an unstable space

In these situations players must pay attention to the difficulties that the surface of play originates. The person must “read” and interpret the indices of this environment to decide on the best option, if it is possible by anticipating his adapted motor actions.

Although there is a scale between the two poles of (domesticated) stable space and (wild) unstable space, the majority of traditional games have been held without a need for specific conditioning of the playground, so they are played in a semi-domesticated or natural space.

Among many examples it is enough to mention the large number of marble games where players take profit of the uncertainty of space; hide and seek games which are played with emotion featuring a search for “a hidden space” on an irregular surface; in the same way, in the games of going up or of moving on an unbalanced trunk trying to reach an object (a prize) has the emotion of being played in an unstable space. In the game of chambot (duel of teams in which one team strike a ball with a stick towards a goal set beforehand together with the rivals; afterwards the defenders can make a defensive action striking the ball in the opposite direction, far away from the goal) the protagonists also join in the fun playing with the irregularities of this natural playground.

In these sorts of situations making decisions, providing reflexive answers and, in addition, displaying adaptive and intelligent motor types of behaviour are very important.

2. From external logic

From the standpoint of external logic to understand the relation with space it is necessary to identify localities in which traditional games are played. Sometimes in the same locality or in villages in the same area we can observe a similar game with great differences concerning its rules (internal logic or text) as well as its socio-cultural conditions (external logic or context).

In a more specific way it is also interesting to identify the relationships originated by local traditional games in different zones of each locality. Thanks to the games people learn how to know all the corners of the locality (streets, squares, indoor-places and outdoor-places in their immediate vicinity).

J. Etxebeste [12] in his study of Basque children’s traditional games observes that the zones where people usually carry out the main social activity are also used for the play purposes; so the indoor and outdoor surroundings of the rural house are the main play venues.

This relationship with local places is often so close that some games use local zones characterized by a very singular local feature. In a recent study carried out in the Lleida area in Spain [13] we have found a number of such features as flagstones located on the central square of Verdu (a small village) and some slabs in front of the town hall of that locality being the main playing surface for “camanxal” (duel of teams of human horses) and “cinquetes” (knucklebones game); the pillars of the Verdu municipal bandstand are the favourite place to play the game of four corners; in the village of Guimera children use a street with a slope to play hopscotch with special obstacles. In other villages, for instance in Campo (Huesca), women usually play a local skittle game called “birllas” at the junction between two narrow streets, using some curious and original playing pieces.

1. From internal logic

Although there are many traditional games that do not need to use objects[ 5], these activities usually take profit of any piece of material found in the surrounding environment. For this reason there is a great amount of different objects and different ways to be used in games.

In psychomotor games the relationships concern the main motor actions: a) throwing games (small objects used with precision: “hoyete”– a table with holes, metal discs, frog, skittles, “patacones” i.e. pieces of cards); bilboquet, also known as ring-and-pin or cup-and-ball, is a game of skill where players try to catch a dangling ball, bone, or ring on a pin or a cup held in the hand; b) games in which objects are moved on a surface: a line, a rectangular surface, “el siete y medio” (seven and half); English quoits; c) jumping (over a pastoral staff with joined feet); d) lifting objects (plough, stone, trunk, bags); e) transporting objects (“xingas”, earthenware jars, bags); and f) other skill tasks (juggling, yoyo).

In sociomotor games of cooperation we can find some interesting examples as well. For instance, skipping games, jumping using elastic ribbons, cat’s cradles is a game where players try to make figures of string woven between the hands; games of passing balls among players trying not to drop the ball to the ground [14].

In sociomotor games of opposition or cooperation and opposition we can find examples of ball games, marbles, lacrosse, tug-of-war and some extraordinary races such as potato-sack race or hobble race.

As we can observe once again, the variety of internal relationships is an important constant or tendency of traditional games.

2. From external logic

The everyday life in the rural societies has been often characterized by taking profit of the resources from the close vicinity of players. The austere, simple and pragmatic life is confirmed by the characteristics of these games.

Once more it is necessary to indicate that the results of a research carried out in the geographical area of Lleida [15] highlight that traditional games are mainly activities that use unspecified objects (66% of cases).

The materials come from the rural environment (home objects) or from public places in the village that people visit daily. For instance, worn buttons used as yoyos, copper coins used in throwing games, or farming shoes or bags used to play different games of races. Sometimes the objects for play are regarded as forfeits used for betting in different games (cards, coins, marbles or spinning tops).

At the same time there are games that use objects from the natural environment. They could be material objects or objects of vegetable or animal origin, e.g. a piece of flagstone in the game of “penillo” (hopscotch), apricot cores used in throwing games, marbles of earthen or excretions of oak; and the game called “cinqueta” with astragal sheep bones.

The objects used in games are often recycled many times before arriving at their playful function. It is the case of the “patacones” made of reused cards; hoops made of wine barrel bands or bicycle wheel rims; rubber shoe heels, or matchboxes for throwing games; and large buttons used as yoyos.

The majority of these objects are often home-made, featuring often personal details depending on individual players. In this context, all the participants are craftsmen presenting their own creations, and this condition points to the interesting educational value of traditional games.

Due to the limitations of resources only a minority of the games (28.6%) require purchased objects, e.g. crystal marbles or ball games. Finally, the research data indicate that when people want to compare the level of their skills of actions they usually play games that use objects, and often display the structures of psychomotor games or sociomotor games of opposition.

1. From internal logic

The educational function of traditional games is also observed in knowledge and skills acquired by different ways of being in relation with their temporal requirements. Regarding the way the games end, two categories can be distinguished:

1.1. Games with a defined end

In these games the duration of the match is subordinated to reach a mark established by the rules. These games have a score system that indicates with clarity the classification of all the players. They are exclusive games (players know their adversaries and their partners) and stable games (no change of team, players are always in the same relation of cooperation or opposition with other players during the match).

In these games the end of the match can be defined according to different criteria:

a) Time-limit games

These games conclude after the passage of an agreed period of time. Then, the players compare how many marked actions have been performed by each protagonist or team. Sports like soccer, basketball or volleyball are the most known examples of such games.

b) Score-limit games

A game stops when one of the players or teams reaches the agreed number of points, e.g. ball games and certain skittle games.

c) Games with a limit by a homogeneous criterion

A criterion of classification to compare the participants’ results is applied in these games. For example, time spent to run a distance, the length reached in some games of jumping or throwing objects (tossing the weight, throwing the hammer), or numbers of trials that a player is allowed to lift a heavy object.

d) Games with score- or time- limit

In these games a match ends if any player has reached a certain number of points or when a period of time has been spent; then players compare the achievements of each participant. It is the case of certain wrestling or combat games such as boxing or judo, when “K.O.” or “Ippon” actions can define the winner of the match before the agreed time has been completed.

1.2. Games without a defined limit

In these games the end of the match is not defined. The motivation of the participants or other external agents (falling night, meal time, beginning of another activity) can mark the end of the match.

The results of the players’ successful actions are not shown in any score, because all successful actions appear and disappear immediately. Such is the case of chase games with the structure of “one against all”; or games with the structure of “one against all – all against one” (for example, the chain tag), or games with an “ambivalent or paradoxical” structure (the four corners or sit down ball).

In the research carried out in the area of Urgell in Lleida the number of identified games with a defined ending is the same as the number of games without a defined ending. Games with a defined ending usually end by the application of a homogeneous criterion or an upper point limit; nevertheless the games with time-limited ending are not common (in fact, this is quite understandable as in rural societies the rhythm of daily actions is not by the clock, but other references to rural life).

In the relational structure of these traditional games, the psychomotor activities and games of opposition (especially individual duels and games with a structure of all-against-all) a defined ending usually ensues, since these are prize games and it is necessary to know clearly who the winner is.

2. From external logic

In the rural societies time runs slow, without the necessity of having to control or measure time in seconds, minutes or hours. In this rural context the temporal requirements are joined by other ways of behaviour that come from:

The rhythm of the work activity: work periods with more or less intensity.

The rhythm of seasons of the year: hotter seasons (spring and summer) and colder ones (autumn and winter).

Religious celebrations: major festivals, Christmas, or the Holy Week.

The school calendar: school months and holidays.

Sometimes when the inhabitants of a locality want to meet each other to celebrate, traditional games are usually present. In fact, in the programs of major festivals a period of time is allotted for traditional games (night dances, competitions after religious services, games before or after meals).

Nevertheless, almost all traditional games, except for sports, do not follow a fixed or pre-established calendar.

The arguments discussed above show that traditional games include plenty of motor and socio-cultural relationships with important effects on the players’ personality.

All the games have an internal logic that orders players to solve different types of problems associated with specific ways of being in relation with other people, space, material objects and time. This ensemble of motor relationships (internal logic) linked to socio-cultural relationships (external logic) offers their actors a specific socialization through the knowledge of some patterns of behaviour, of local symbols, and of social representations. All these things have a deep penetrating effect on rural inhabitants.

Let us focus on another example involving fictitious students. Oriol, Carlos, Marta and Ares are primary school pupils who have decided to play a traditional game called captive balloon[ 6]. The internal logic of this game divides the players into two teams. The players must use a balloon to perform actions, and they are not able to leave the zone from which they start to play, except if they are “murdered”. Passing the balloon to a partner, throwing the balloon to an adversary, intercepting the balloon, feinting, and clearing the balloon are examples of specific motor actions in this game.

Although the rules are the same for Oriol, Carlos, Marta and Ares, all of them play in an individualized way. That is not due to the colour of their hair or to their height, but depends mainly on the way each player interprets (“reading”) the internal logic of the game while performing motor actions.

Oriol is the boldest player who takes most risks; he always wants to catch the balloon. Marta who is a more calculating player decides to secure her motor actions, without stopping paying attention to all her adversaries and partners. Carlos is always hesitant and he is not able to anticipate his opponents’ actions and, in addition, he is the first to be eliminated. Ares likes to pass the initiative to the others and she often gives them the balloon.

All these four students read, decipher, interpret “the grammar” (internal logic) of the game in a different way, by performing individual motor actions. In these conditions the abstract concept of motor action, become a personalized concept of motor behaviour [17].

The subjective way of each student to perform the motor actions is associated with the systemic and uniform concept of motor behaviour. This concept shows an extraordinary way that teachers should put in practice when they want to improve and optimize their students’ personality. Parlebas [18] defines this term as significant organization actions and reactions of a person facing a motor situation. In the traditional game of captive balloon, the motor behaviour of each student incorporates whatever is observed from the outside (like a sequence of frames recorded by a camera, i.e. the way of making a feint at throwing or giving the balloon to a partner). Nevertheless, at the same time, the concept of motor behaviour takes into account the significance that this playful activity has for each player, by considering its affective, cognitive, and social dimensions.

Any person, understood as an intelligent system, acts in a different way in each game, displaying individual motor behaviour. Any motor behaviour provides a strictly physical or motor response, but also constitutes one’s own personal experience (joys, fears, perceptions), and finally, it is a true mirror where we can observe how the players are living or feeling their life.

Now, let us take a closer look at Oriol and Carlos, two players of “the captive balloon” game. It has already been stated that Oriol is the bolder one, he takes many risks in his actions, and he always wants to catch the balloon. On the other hand, Carlos is more reserved and hesitant once he gets hold of the balloon, so he usually gives it to his partners. In a few minutes, these two pupils decide to perform another activity: a throwing game (using metal discs). They must throw four metal discs at a cylindrical and vertical object that is put in the ground, 5 meters away, to knock it off. While Oriol, who is more impulsive, has difficulties with his concentration and throws the metal discs with precipitation, Carlos, more moderated, concentrates, adjusts the position of his body, breathes deeply and throws the metal disc with precision.

The captive balloon and the throwing game using metal discs are two traditional games with very different internal logics. In addition, they generate motor behaviours of different nature (in “captive balloon” the motor types of behaviour are associated with decision making and cognitive capacities, while in the game of throwing metal discs the emergent processes are associated with automatism, concentration, and perseverance). The evaluation of Oriol’s and Carlos’ motor behaviour allows us to indicate that Oriol and Carlos need a different pedagogical intervention in order to optimize their motor knowledge and their personality.

Oriol needs to improve his motor behaviour of concentration and perseverance, whereas Carlos should optimize his behaviour associated with a more committed decision-making process. Oriol can improve his motor behaviour by playing psychomotor traditional games in a stable medium, while Carlos could be helped by playing traditional games with making decisions associated with a broad variety of forms of communication with others (reminded that the games can have an exclusive and ambivalent network; and be stable or unstable, too), as well as by participating in various role-playing games[ 7] (associated with the need to take the initiative).

By applying the principles of motor praxeology, we know that each game has a specific internal logic and educates the players in some specific motor behaviour. Some examples illustrating these ideas are indicated below:

Psychomotor traditional games played in a stable medium tend to generate situations associated with automation of motor stereotypes and also reproduction of a specific technical execution of motor actions with programmed repetitions. These games require a rational use of physiological sources to perform actions with the optimal effort and effectiveness. These activities are very effective in the improvement of motor behaviours related to perseverance, personal effort and sacrifice (for example, throwing, jumping or racing games). Learning from these games can be also transferred to other situations of daily life, mainly to those situations where the result depends exclusively on our own response (effort in work, perseverance to learn how to read or write, sacrifice of leisure time to repair something at home in order to have more comfort, etc.).

Traditional games of collaboration offer an infinity of motor situations which generate behaviour associated with motor communication, compromise, generous sacrifice in collaboration, taking initiative, coming up with original and collective answers and respecting others’ decisions. As in daily life, the group is autonomous to decide on the best answer for the common challenge. For example, we can find these sorts of social situations when it is necessary to solve social problems such as violence, lack of water, discrimination, etc. These difficulties are impossible to solve without the cooperation of all the group members.

Antagonistic traditional games (of opposition or collaboration-opposition) require the players to make decisions, anticipate, decode messages sent by other people, and define motor strategies. This sort of games can be used to teach behaviour associated with challenge, competitiveness or with resolution of problems. It will be interesting to work with all the different structures of internal logics by playing games of opposition and co-operation opposition, in order to optimize this type of motor behaviour. For example, in games where players can change teams (games with an unstable motor communication network such as chain tag or sparrow hawk or hen-fox[ 8]) the defeat is not clear because all the players finish the game by becoming part of the same team.

Games played in an unstable medium, in the psychomotor or sociomotor version, require that players “read”, decode and adapt to the difficulties of the ground. This type of situations improves adaptive motor behaviour associated with intelligent effectiveness, decision making, anticipation and risk. The traditional games played in the rural medium (chambot, hide-and-seek games, games of orientation) can serve as examples.

With reference to the reflections and concepts discussed above, some pedagogical applications based on the relations activated by the internal logic and the external logic of traditional games should be described. These examples function to serve to reveal the educational potentiality of traditional games and sports.

1. Playing with internal logic. The motor richness of traditional games

The Department of Culture of the Government of Catalonia decided to produce a documentary series about traditional games in order to popularize some pedagogical values of these activities among the schools of this region.

After having considered different options the idea of compiling a plain “list of games” was excluded, as we decided to annotate all the games. The first episode concentrated on the motor richness of games with the purpose to offer some examples of traditional games played in Catalonia displaying a great variety of internal logics and ways of motor communication.

Considering that motor richness is one of the most important treasures of traditional games, and that they are in fact laboratories of motor, affective and social relationships we decided to use some vivid examples of games of different categories from the standpoint of motor relationship (psychomotor games, games of cooperation, opposition and cooperation-opposition). We assumed that any traditional game, played by children or adults, spontaneous or sportive modality, had the same entity and educational importance. In the motor field there are no better or worse games as such, but they are only good or bad games in terms of achievement of some specific goals or challenges.

The documentary was entitled “Jocs tradicionals a Catalunya” (Traditional games in Catalonia) (1999) and was 31 minutes long. It was shot in different villages in Catalonia, with participation of primary and secondary school students and the students of the University of Lleida (INEFC-Lleida).

2. Playing with external logic. A visit to medieval Lleida (Spain) by way of traditional games

In 1998 the cultural association “Ateneu Popular de Ponent of Lleida” organized a recreational event with the intention to help Lleida inhabitants to get to know Lleida of the medieval times. The event was held repeatedly for several weekends. Each weekend was devoted to one topic and cultural event from that historical period, including work, the life of the Jewish community, ceramics, the plague, and traditional plays and games.

The theme of traditional games was coordinated by Costes and Lavega [18][ 9] who tried to use these sorts of activities in order to captivate the Lleida environment of the Middle Ages. We decided to design a playful, guided tourist visit using examples of traditional games that were played in some most emblematic zones of the city. So we “played” with the external logic of traditional games (places of the town) in order to display the motor and socio-cultural relationships associated with traditional games in the Middle Ages.

The above experiment was addressed to all the people of the city who wanted to follow this activity. For the purpose of the visit different zones (squares, streets) were set up in which a group of university students of physical education (INEFC) and students from other University faculties played various traditional games. The public was observing the development of a game and at the same time they were listening to comments on its rules, socio-cultural aspects and curiosities. After a few minutes, players and public walked to another zone. The event was accompanied with medieval music, jugglers, and the players were wearing historical clothes

Little by little, more and more people joined the visit, by observing the activities, listening to explanations and playing some games. Firstly, the “old ball street” was reconstructed. This street used to run beside the St. John’s Church where people usually played a ball game of opposition. Afterwards people could observe the “Belit” (game played with a stick with sharpened ends) – a team game of cooperation-opposition, being one of the most favourite games of the university students of that time. Next, a game of cooperation-opposition called “Xurra” similar to ancient hockey was played according to the original rules (e.g., the captains of both teams stopped the match and agreed on a new rule in a conflicting situation). Other games included the game of “Tella” (a quoits game) and a well-known betting game that used to be often banned in the past. Spectators could also see other games such as knucklebones, spinning tops, hopscotch, and the game of “vejiga of cerdo” (‘pig bladder’) similar to the ancient game of soule played between two zones of the city, combat games with the use of weapons, and a local skittle game accompanied with magic and religious symbols.

This playful visit to the principal streets, squares and surroundings of public buildings (churches or the town hall) allowed everybody to get acquainted with the playful Lleida of the Middle Ages. Following Parlebas [19], the internal logic of these games uncovered social messages and symbolisms and at the same time showed representative forms of organization of people of that historical period.

3. Pedagogic experience based on the traditional games in the Catalan Pyrenees (Playing with internal logic and external logic)

This experiment was organized similarly to the ones discussed above. More than two primary school students (aged 8-11) from the area of Pallars Sobira (Lleida) participated in this event.

The preliminary steps were made two years before local traditional games from the area of the Catalan Pyrenees began to be thoroughly studied. After identifying and analysing the internal logic (rules) and external logic (socio-cultural conditions) of the games we offered to coordinate this recreational event in the village of “Ribera de Cardos” on May 29th, 1998. The previous research was very useful in identification of different games according to a variety of internal logics and also of particular aspects of the context (external logic).

In this experience we tried to combine two binary aspects of the games: text and context, and internal logic and external logic. The students were divided into groups of ten. They visited different zones of the village where they could play one identified traditional game in that village. During this activity some local inhabitants were not able to resist the temptation to approach the students and play some well-known games with them.

Through this pedagogical activity all the students could become acquainted in a playful way with the village of Ribera Cardos. These students played some of the most representative games, and displayed a large variety of motor relationships with pupils from other villages. In addition, they could find themselves closer to inhabitants of that village and receive the important socio-cultural knowledge by acting in the same place where inhabitants received this learning some years ago.

4. The first festival of traditional games. Campo and Lleida 2002 (Playing with internal logic and external logic)

The final example included organization of the first festival of traditional games in the village of Campo (Huesca, Aragon Pyrenees) on May 15th, 2002 by the Museum of Traditional Games of Campo and INEFC-Lleida (University of Lleida).

About 200 university students of physical education from the INEFC-Lleida and 240 school students (aged 11-12) from the same geographical area participated in this experience. Forty university students signed for an optional course named “To live a great traditional game” and they learnt to design, organize and evaluate this great and playful event. The other university participants were first year physical education students, and participation in this activity was mandatory for them as part of the academic course “Theory and practice of play”.

For most students this was the first time they ever participated in a great event based on traditional games. For this reason the 1st Festival of Traditional Games whose major theme was a magic trip to the country of traditional games had two complementary orientations:

Travel by the external logic of traditional games (in the morning). The university students of INEFC were divided into six groups and played the games in six zones (stations); the school students were also divided into six groups in order to participate in a parallel circuit with six stations as well. The organization of these six zones helped all the students to explore some topics related to the socio-cultural conditions of traditional games:

Traditional games and protagonists: male and female games, games for children and adults.

Traditional games and moments: the festive environment of games.

Traditional games and material: hand-making playing objects.

Traditional games and magic-religious beliefs: play, mystery, ritual.

Traditional games and sport: organization of a little Olympic competition.

Traditional games and museum: once a group arrived at a museum, each player was to locate an object in the museum related to one of the zones, and learn about it. Afterwards, the participants visited the museum all together, sharing information about the located objects.

Travel by the internal logic of traditional games (in the afternoon). Pretending they were at a big kermesse or village fair, the participants could complete their morning trip playing some of around 100 traditional games. These games were divided according to the criteria of their internal logic: a) psychomotor games (jumps, throws, races); b) games of cooperation (skipping ropes, dances), c) games of opposition (individual duels, all against all, one against all), and d) games of cooperation-opposition (team duels, N-teams, two against all – all against one, paradoxical games).

The students were supposed to play a minimal variety of games of the different categories, to ensure many years of “magic order”. The conditions to play these games indicated that it was necessary to establish contact among eight students from different groups (university students and primary school pupils). The magic trip by the external logic and the internal logic allowed all participants to win a magic gift and share a special and unforgettable event with other people.

Final remarks

In this article we have tried to show the extraordinary pedagogical assets of the traditional games. These assets can be applied in formal and official programs of education, as well as in unofficial or formal events.

Regardless of the age, sex or nationality, when some people play together they start to share an important ensemble of motor, cognitive, emotional, social and cultural relationships. In this way, the great richness and variety of internal logics of traditional games can justify the statement that the game itself is the best teacher for any student.[ 10]

At the same time if we apply features of the socio-cultural context of traditional games with rigor, sensitivity and coherence, we will be able to provide unforgettable learning opportunities, making people grow and share the playful knowledge.

[1] Lipoński, W., World Sports Encyclopedia, Ozgraf (Poland), Oficyna Wydawnicza Atena, UNESCO, 2003.

[2] Parlebas, P., Juegos, deporte y sociedad. Léxico de praxiología motriz, Barcelona: Paidotribo. (Games, sports and societies. Motor Praxeology Vocabulary), Paris, INSEP 2001, p. 201.

[3] Lankford, M.D., Hopscotch around the world, New York, a beech tree paperback book, 1996.

[4] Parlebas, P., op.cit., p. 223.

[5] Parlebas, P., “Jeux d’enfants d’après Jacques Stella et culture ludique au XVIIe Siècle” (Children games of Jacques Stella and playful culture in the 17th century), (in:) proceedings book of the Festival d’Histoire de Montbrison, 1988, pp. 321-353.

[6] Ibid, p. 227.

[7] Lavega, P., “Les jeux et sports traditionnels en Espagne. Quelques notes a propos de l’identité, le contexte et la fonction culturelle, a partir d’une vision pluridisciplinaire (transversale)” (Traditional games and sports in Spain. Some notes in connection with the identity, context and cultural function, from a (transverse) multi-disciplinary vision) (in:) J.J. Barreau, and G. Jaouen, eds., Les jeux populaires eclipse et renaissance. (Popular games: eclipse and rebirth), Morlaix, Falsab, 1998, pp. 111-128.

[8] Lavega, P., Los juegos y los depotes populares-tradicionales (Traditional and folk games), Barcelona, Inde, 2000.

[9] Lagardera, F. & Lavega, P., Introducción a la praxiología motriz, (Introduction to motor praxiology), Barcelona, Paidotribo, 2003.

[10] Lavega, P. and Al. “Estudio de los juegos populares/tradicionales en la comarca del Urgell” (The study of traditional popular games in the area of Urgell–Catalonia in Spain). Three Studies entrusted by the Centre of Promotion of Catalan Popular and Traditional Culture. Inventory of the Ethnological Patrimony of Catalonia. Barcelona. Department of Culture, 2001, 2002 and 2003.

[11] During, B., La crise des pédagogies corporelles. (The crisis of body pedagogies), Paris, editions du Scarabée, 1981.

[12] Etxebeste, J., “Reflexiones sobre la educación física de hoy a la luz de las características de la cultura tradicional vasca” (Reflections about physical education considering the traditional culture of the Basques) (in:) F. Lagardera & P. Lavega (eds), (2004) La ciencia de la acción motriz, (The science of motor action), Lleida, Universitat de Lleida, 2004, pp. 119-138.

[13] Lavega, P. and Al., 2001, 2002, 2003, op.cit.

[14] Lagardera, F. & Lavega, P., “conductas motrices introyectivas y conductas motrices cooperativas: hacia una nueva educación física” (Introjective motor behaviour and cooperative motor behaviour: towards a new physical education), (in:) F. Lagardera & P. Lavega (eds) [2004] La ciencia de la acción motriz, [The science of motor action], Lleida, Universitat de Lleida, 2004, pp. 227-254.

[15] Lavega, P. and Al., 2001, 2002, 2003, op.cit.

[16] Lavega, P. & Lagardera, F., “La invención y la práctica de juegos espontáneos en los alumnos universitarios de INEFC-Lleida. Estudio de sus características estructurales” (The invention and practice of spontaneous games in university students of physical education in the faculty INEFC-Lleidda. Study of structural characteristics) awarded research by INEFC-Lleida, 2000.

[17] Lavega, P., “Aplicaciones de la conducta motriz en la enseñanza” (Applications of motor behaviour in education) (in:) F. Lagardera & P. Lavega (eds) [2004] La ciencia de la acción motriz, [The science of motor action], Lleida, Universitat de Lleida, 2004, pp. 157-180.

[18] Costes, A. & Lavega, P., “Els jocs populars-tradicionals a la Lleida de l’edat mitjana.” (traditional games in Lleida in Middle Ages) (in:) Ateneu Popular de Ponent (ed.) Coneixes la teva ciutat...? La ciutat baix medieval (segles XIV-XV). (Do you know your city? The Medieval Town (14th-15th century)), Lleida, Ateneu Popular de Ponent, 1998, pp. 133-146.

[19] Parlebas, P., Les jeux transculturels (The trans-cultural games) in Demeulier, J. (org.), “Vers l’Education Nouvelle-Reveu des Centres d’Entrainement aux Méthodes d’Education Active. Jeux et sports”, 2000, 494, pp. 6-7.

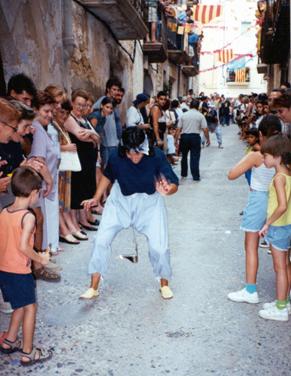

Fig. 1. Traditional games are an excellent way to sociabilize people. People playing traditional games are players who uses the body language to show the deepest part of their personality and culture.

Fig. 2. Example of traditional game of cooperation in which players share a common goal. In these type of games all the players are winners.

Fig. 3. Many traditional games have open democratic rules that allow players to participate without conditions of age, sex or ideology.

Fig. 4. In this picture, as well as picture 5 mikado game gives to players (adults and children) an excellent opportunity to share an optimal experience.

Fig. 5. Example of some materials to play traditional games. All these objects are got from the daily environment of rural players showing an excellent and ecological way of recycling.

Fig. 6. Example of skitlle game from Brittany (France). In this traditional psychomotor game players must solve the motor actions without being helped by anybody.

Fig. 7. Example of an original race played in Prat de Comte (Catalonia, Spain) during its main party. Players must keep the fire on while they are running, if not they must stop to get fire before running again.

[ 1] Wojciech Lipoński World Sports Encyclopedia [1].

[ 2] Expressions such as motor game, motor praxeology or motor behaviour are to mean physical activities that need participation of the body. These activities are quite different from social games or table games in which the actors only participate on a cognitive level.

[ 3] Parlebas (2001) creates an (universal) operational model called the network of motor communications to study the subjacent structure of games related to the nature of motor interactions determined by the rules.

[ 4] See Guillemard, G. et al. Las cuatro esquinas de los juegos. Lleida, Agonos; original French version: Aux 4 coins des jeux (The four corners of play) Paris, Du Scarabée, 1988; Bordes, P. et al. Fichier de jeux sportifs. 24 jeux sans frontiere. (File of sport games. 24 games without borders), Paris, CEMÉA, 1994.

[ 5] In a study carried out with physical education students from INEFC-Lleida, we observed that girls and also mixed groups (boys and girls) played almost always situations based on traditional games in which they were asked to improvise play situations without being able to make use of objects. P. Lavega & F. Lagardera [16].

[ 6] In this traditional game each team has one zone for “live players” and another for “dead ones”. If a player throws the balloon and strikes the body of an adversary with it, and he or she is able to catch it, then the throwing player is eliminated and enters the dead players’ zone. If this action is performed by a dead player, he becomes a “live” player and enters the live players’ zone. The team which is able to eliminate all the opponents wins.

[ 7] The concept of the role in a game is a set of rights and prohibitions associated with one or more players, defined by the rules of the game. For example, in soccer or handball there are two roles: goalkeeper and field player; whereas the rules of basketball authorize all the players to perform the same actions in the same conditions, consequently there is just one role: the field player.

[ 8] Gavilan (“hen-fox”) is a game in which a player standing in the center (‘hen-fox’) of the playing area tries to “capture” the other players only with side displacements when they try to run to the other side of the playground. The captured players then help the hen-fox to capture other opponents until all the players are captured.

[ 9] Professors of the INEFC-Lleida (Faculty of Physical Education of the University of Lleida).

[ 10] For more on applications of motor praxiology or science of motor action see www.praxiologiamotriz.inefc.es (International Virtual Centre of Documentation in Motor Praxiology).