Vol. 10 No. 2

UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION IN POZNAŃ

Poznań 2003

Table of Contents

- PART I HISTORY OF PHYSICAL CULTURE AND SPORT

- THE MEANING OF THE OMADA. THE NOTIONS OF GROUP AND SPORT TEAM DURING THE EPIC PERIOD

- DANCE AS A BASIC CULTURAL ELEMENT AND MODE OF EDUCATION IN ANCIENT GREECE

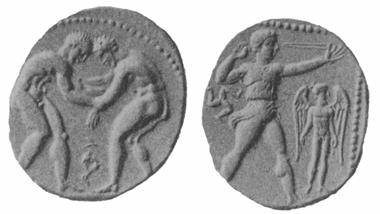

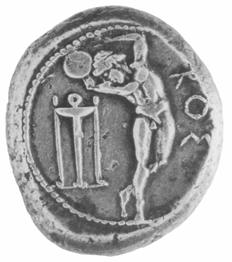

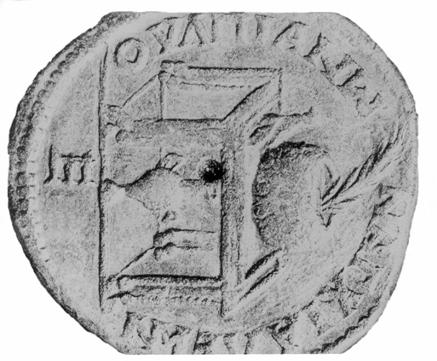

- ANCIENT COINS AS CARRIERS OF THE CLASSICAL OLYMPIC AND ATHLETIC IDEAS

- EUROPEAN FENCING SCHOOLS AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF POLISH FENCING BEFORE 1939

- THE ATTITUDE OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH TOWARDS SPORT AND OTHER FORMS OF PHYSICAL CULTURE IN POLAND IN THE PERIOD OF STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATION (1989 – 2000)

- ABSTRACT

- THE ATTITUDE OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH TOWARDS PHYSICAL CULTURE IN THE PERIOD OF III REPUBLIC (UP TO 2000).

- THE PASTORAL LETTER OF THE EPISCOPATE OF POLAND OF FEBRUARY 04TH, 1991 ENTITLED “ON THE DANGERS IN HEALTH AND SPORT CULTIVATION”

- THE PASTORAL LETTER OF THE EPISCOPATE OF POLAND ON “THE CHRISTIAN QUALITIES IN TOURISM” DATED 16TH– 18TH MARCH, 1995

- REFERENCES

- PART II LEISURE AND RECREATION

- PART III METHODOLOGY OF TEACHING

- A PROPOSED MODEL FOR EVALUATION OF OLYMPIC AND SPORT EDUCATION PROGRAMS

- ABSTRACT

- THE NEED FOR EVALUATION IN EDUCATION AND IN OLYMPIC AND SPORT EDUCATION PROGRAMS

- THE NECESSITY FOR EVALUATION OF THE PROGRAMS OF OLYMPIC AND SPORT EDUCATION

- AIMS AND OBJECTIVES OF EVALUATION FOR OLYMPIC AND SPORT EDUCATION

- TYPE AND MODEL SELECTION OF EVALUATION FOR THE O.S.E. PROGRAMS

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- PART IV HUMAN BIOLOGY AND EXERCISE PHYSIOLOGY

- PART V BOOK REVIEWS

- NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS

Editorial Board

Diethelm Blecking, privat-Dozent, Freiburg, Germany

Stefan Bosiacki, University School of Physical Education, Poznań, Poland

Lechosław B. Dworak, University School of Physical Education, Poznań, Poland

Janusz Feczko, Academy of Physical Education, Katowice, Poland

Anthony C. Hackney, University of North Carolina, USA

Masahiro Kaneko, Osaka University of Health and Sport Sciences, Japan

Krzysztof Klukowski, Air Force Institute of Aviation, Warsaw, Poland

Stanisław Liszewski, University of Łódź, Poland

Ioannis Mouratidis, Aristotelean University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Krystyna Nazar, Institute-Medical Research Centre, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland

Wiesław Osiński, University School of Physical Education, Poznań, Poland

Andrzej Pawłucki, Jędrzej Śniadecki University School of Physical Education, Gdańsk, Poland

Łucja Pilaczyńska-Szcześniak, University School of Physical Education, Poznań, Poland

Wiesław Siwiński, University School of Physical Education, Poznań, Poland

Włodzimierz Starosta, University School of Physical Education, Poznań, Poland

Atko Viru, University of Tartu, Estonia

Chairman of the Publishing Board: ŁUCJA PILACZYŃSKA-SZCZEŚNIAK

Editor in Charge of Translations: TOMASZ SKIRECKI

Front cover: A ball player, relief in the collection of the National Archeological Museum in Athens; photograph by courtesy of the International Olympic Academy.

Indexed in:SPORTDiscus Ulrich’s International Periodical Directory

Editorial Board Address: University School of Physical Education Królowej Jadwigi 27/39 61-871 Poznań, POLAND tel: 835 54 35; 835 50 68 Fax: 833 00 87

Computer page layout: EWA RAJCHOWICZ

Printed in Poland © Copyright by Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego w Poznaniu

ISBN 83–88923–32–3

ISSN 0867–1079

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission from the Publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism or any form of scientific commentary.

Dział Wydawnictw AWF Poznań. Zam. 17/03

Table of Contents

- THE MEANING OF THE OMADA. THE NOTIONS OF GROUP AND SPORT TEAM DURING THE EPIC PERIOD

- DANCE AS A BASIC CULTURAL ELEMENT AND MODE OF EDUCATION IN ANCIENT GREECE

- ANCIENT COINS AS CARRIERS OF THE CLASSICAL OLYMPIC AND ATHLETIC IDEAS

- EUROPEAN FENCING SCHOOLS AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF POLISH FENCING BEFORE 1939

- THE ATTITUDE OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH TOWARDS SPORT AND OTHER FORMS OF PHYSICAL CULTURE IN POLAND IN THE PERIOD OF STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATION (1989 – 2000)

- ABSTRACT

- THE ATTITUDE OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH TOWARDS PHYSICAL CULTURE IN THE PERIOD OF III REPUBLIC (UP TO 2000).

- THE PASTORAL LETTER OF THE EPISCOPATE OF POLAND OF FEBRUARY 04TH, 1991 ENTITLED “ON THE DANGERS IN HEALTH AND SPORT CULTIVATION”

- THE PASTORAL LETTER OF THE EPISCOPATE OF POLAND ON “THE CHRISTIAN QUALITIES IN TOURISM” DATED 16TH– 18TH MARCH, 1995

- REFERENCES

NIKOLAOS BERGELES, DIMITRIS HATZIHARISTOS

National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Correspondence should be addressed to: Nicolaos Bergeles, Faculty of Physical Education & Sport Science, Department of Sport Coaching, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Key words: Ancient Sport; Team Sports; Homer; Hesiod; Homeric Hymns; Orphic Hymns.

The following study is aimed at examining the meaning of the “omada” as it was perceived by ancient Greeks, through the works of the epic cycle of Greek Grammatology. The study has been conducted on the basis of contemporary operational definitions and group characteristics that certify the perception of existence of a functional group or team. A literary approach was adopted to find words suggesting the meaning of a common action or work of a number of subjects possibly constituting a group. Although the meaning of sport team was not defined, various types of groups were identified. Chariot crews and playing teams functioned as sport teams. In the Odyssey music and dancing teams, hunting parties, and entertainment teams combined with acrobatics can be observed. On the other hand, war parties, military operation teams, and groups of gods and deities can be found in the Iliad.

The archaeological spade and the study of ancient texts have brought to light sufficient evidence on all the aspects of the long-lasting ancient Greek civilization. Ancient Greek literature is divided into nine periods: from the earliest one – the epic period – to the Roman period [1]. The former includes primarily the Iliad and the Odyssey by Homer; the Theogony, the Works and Days, and the Shield of Heracles by Hesiod; and secondarily the HomericHymns, whose date, origins, collector and author remain unknown. Exception is the Hymn to Apollo, which Thucydides [2]ascribes to Homer. The Orphic Hymns can also be included in this period as, according to Hasapis's study [3], their contents can be traced back as far as to the 14th cent. BC. It is commonly recognized that there had been other poets before the Homeric period as well, e.g. Orpheus, Linos, Mousaios, Efmolpos, Thameris and others, whose works, however, have not survived.

Information about sport games is mainly provided by the Iliad and the Odyssey. Rhapsody 23 of the Iliad describes funeral sport games held in honour of the late Patroclus [4]. Significant information on sport games is also included in Rhapsody 6 of the Odyssey [5], in which references are made to games organized by the King of Phaiakon, Alcinous, in honour of his guest Odysseus. The same rhapsody contains examples of kinetic activities, which took place in public locations or in settings of the cities’ lords, e.g. shot put, dance and several gymnastic exercises, and other games. The examination of relevant literature reveals that no study with a psychological approach seems to have been conducted on any kinetic group activity or on any athletic or non-athletic situation demonstrating group characteristics in the broad or strict sense of the term.

Social psychology, which studies in a systematic way the human group in its various forms evolved in the mid-20th century. Social psychologists, in order to suggest types of positive interventions in various social and work groups, studied the small group, in which they identified several characteristics and formulated operational definitions for the term group. The purpose of the present study is to investigate the characteristics displayed in the meaning of the omada (group/team), with particular emphasis on the notion of the sport team, in the way it was perceived during the epic period.

For the aforementioned purpose, texts from the epic period were studied on the basis of contemporary prevalent operational definitions and group characteristics that were identified in actions, perceptions, feelings and intentions of the subjects, clearly described in the ancient Greek language. A combination of these characteristics indirectly indicates the existence of a functional group. Also, the study was simultaneously conducted using literary research in which individual words were studied bearing refe-rence to a common action or work of a number of subjects possibly constituting a group. In other words, attention was given to simple or composite words in various forms of speech that signified the group character of the situation.

The way in which the group is perceived, and which constitutes a form of a person’s transition to society, according to Adorno and Horkaimer [6], is theoretically seen for the first time in Zimmel [7]. In the broad sense the term team can be comprehended either as a community of interests or as a random gathering of people; as a self-conscious community, or as a group of people with common characteristics. Nevertheless, the science of social psychology has attempted to extract, on the basis of certain distinct criteria, an identical core, which sometimes becomes typical, with only one meaning in a multi-meaning reality. A group “can be temporal or durable, organized or not, as long as it is in effect the same influence and common conscience between its members” [8] or “its members possess team spirit” [9].The same definition is given by Geiger who says that, “a number of individuals constitutes a group, when they are related to each other in such a way that each person feels part of the common we” [10]. In American sociology, distinguished for its behavioral approach, a typical meaning of the term group seems more objective: “It is a number of individuals, which have common interests, are intermotivated, have common faith in the group, and participate in common activities. Their number may range from a small family, composed of parents and a child…to a national group of millions of people” [11]. This definition includes every kind of social morpheme, so that Weise in Germany proceeded in dividing groups on the basis of the distance of individuals from those groups [12]. Particularly interesting is the small group, which Homans defines as “every person can be related with every other, directly and personally and without the intervention of somebody else” [13].

Cooley [14] calls small groups primary groups, whose main characteristics are very close and frequent contacts of persons that constitute them, and intense interactions to the point where the person’s personality is developed, or can almost be integrated. Those groups are natural morphemes in the narrow social context, in which people who constitute a family, neighborhood’s company of children, sport groups, educational groups and other ones live. Secondary groups consist of large numbers of people, e.g. nation, political party, social class.

A notional conflict has been observed between groups defined either as the sum of people constituting it, or as a separate entity. The group as a special entity comprises of “units of social life that exist and are preserved beyond the come and go of individual people” [15] and “in short, they have a unified and self-defined life, according to the meaning of individuality” [15]. In the 1920s, the group was interpreted as a phenomenon that derived from the contrast between the atomistic and the catholic perception. Since the appearance of Gestalt psychology, a perception that the individual’s relation to the group is functionally mutual has constantly prevailed [16]. Lewin, as one of the first founders of that theory, and of the “field theory” in particular, stated that “a group is best defined as a dynamic whole of people based rather on interdependence than on its members’ similarity” [17].It has also been stated that “a group is a number of interacting and sociometrically related individuals” [18], or a cycle of persons of small or large number that act together and simultaneously, because of the common consciousness of the situation. On the basis of group dynamics, Cartwright and Zander examined many definitions and determined that, “a group is a collection of individuals that are related to each other in such a way that they are interdepending in some significant degree” [19]. Johnson and Johnson summarized that, “a group is two or more individuals in face-to-face interaction, each aware of their membership in the group, and each aware of their positive interdependence as they strive to achieve mutual goals” [20].

Numerically, the smallest group is considered to be composed of at least two persons, who believe to be part of the same group [21]; “two or more persons who are interacting with one another in such a manner that one person influences and is influenced by another” [22];or “a set of individuals who share a common fate, that is, who are interdependent in the sense that an event which affects one member is likely to affect all.” [23].

In the case of sport teams, which constitute the most representational examples of small groups, the following definition was formulated: “the most important characteristics of a sport team is a collective identity, a sense of shared purpose, structured patterns of interaction, structured methods of communication, personal and task interdependence, and interpersonal attraction” [24].According to the theory of group dynamics, some of the most significant elements of a team’s characteristics are that they engage in frequent interaction. They define themselves as members and they are defined by others as belonging to the group; they share norms concerning matters of common interest and they participate in a system of interlocking roles; they identify with one another as a result of having set up the same model-object or ideals in their superego; they find the group to be rewarding and satisfying their needs, they pursue promotively interdependent goals or common goals, they have a collective perception of their unity, they tend to act in a unitary manner toward the environment, and they are characterized by cohesion, unity and group mind [25].

A representative type of sport team was a two-member chariot crew that participated in chariot games. In Rhapsody 23 of the Iliad, chariot games are held in honour of the late Patroclus. Referring to those games, Nestor narrates to Achilles the famous chariot team of Actor’s two sons “Twin brothers they were – one drove with sure hand, while the other plied the whip” [26]. The two-member crew constitutes the minimum numerical limit to define a group [27], while a group consisting of few members is a positive element for the development of intense interaction between its members. Basic characteristics of that team were the interdependent roles, since one was whipping the horses and the other was leading them, as well as the recognition by third people – in that case King Nestor, who was obviously recognized by all the inhabitants of Pylos and other regions. The fact that this particular team was characterized as invincible, shows that it was an established one, resulting in its permanence. This finding stresses the characteristic interaction developed between its members. Moreover, Nestor stresses the fact that he was defeated by those two in a chariot game, because they wanted to win to get prizes, which were the most valuable ones in that game. The common perseverance to the cause from both riders can be identified here, which is the main component of cohesion that made the team perform more effectively in those games and ultimately led them to victory. Also, their recognition by others furnishes evidence that there were many two-member chariot teams competing against each other. In the games in honour of Patroclos, references were made to competitive one-member chariot crews, thus not constituting a team.

A team in a group game can be found in Rhapsody 6 of the Odyssey, where Homer describes Nausicaa’s play with her handmaids, “Then when they had had their joy of food, she and her handmaids...fell to playing at ball, and white-armed Nausicaa was leader in the song…And even as Artemis,…, daughters of Zeus who bears the aegis, share her sport,…So then the princess tossed the ball to one of her maids; the maid indeed she missed, but threw it into a deep eddy,…” [28].

Artemis playing the same game points to the fact that it was an established game. The team's purpose in that game was entertainment and its characteristics referred to the interdependence of the leader and the members, since for the game to be in effect the ball should be accurately sent from one member to the other, while the latter should catch the ball in the air. The interaction feature obviously results from the team’s permanence and frequent contact between members. Nausicaa’s team game with her handmaids is described by Odysseus to her father Alcinous, King of the Phaecians, having been received in his palace: “Then I saw the handmaids of your daughter upon the shore at play” [29]. The same game was also cited in the Hymn to Demeter [30], where Persephone was carelessly playing in the field with a group of goddesses, as her own mother Demeter was narrating, just before being kidnapped by Pluto. Indeed, the teammates of Persephone were cited by their names “All we were playing in a lovely meadow, Leucippe and Phaeno and Electra and Lanthe, Melita also and Lache with Rhodea and Callirhoe and Melobosis and Tyche and Ocyrhoe, fair as a flower, Chryseis, Ianeira, Acaste and Admete and Rhodope and Pluto and charming Calypso; Styx too was there and Urania and lovely Galaxaura with Pallas who rouses battles and Artemis delighting in arrows: we were playing and gathering sweet flowers in our hands, soft crocuses mingled with irises and hyacinths,…” [30].

Studying the previous references it could be asserted that they concerned teams composed of a few members featuring friendly relationships among them like Persephone’s team, or compulsory team membership, e.g. Nausicaa’s team of handmaids obliged to serve and entertain the princess. However, that does not exclude a possibility that friendly relationships existed between the princess and her handmaids. In any case, those were teams of kinetic recreation, of a small and established number of members, famous, as in the case of the Hymn to Demeter, for playing together with the ball, singing and at the same time picking flowers. The fact that Nausicaa trusted her handmaids shows that their trust had been tested over time, and therefore a positive attitude had been developed among them. On the other hand, the handmaids were attracted to the princess because of her rank, which in current theories is referred to as the individuals’ attraction to individuals of higher social status [31]. In regard to Persephone’s team, the mutual attraction between members of the team derived from the same social class, which was the divine being of her teammates [32]. Furthermore, a frequent contact could be revealed, which is considered to be a prerequisite for the development of interaction. This characteristic feature of frequency in a long duration constitutes a more cohesive group, as it can be observed in Persephone’s seizure. Because, in order for Pluto to plan her seizure, the daily habits of the young goddess should have been watched and recorded.

A type of team aimed at the entertainment of the palace people, with special features like music, dance and gymnastic exercises is described in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, in Hesiod’s Shield of Heracles, as well as in an anonymous poet’s Hymn to Apollo. In the Iliad’s Rhapsody 18, devoted by Homer to the forging of Achilles' weapons by Hephaestus, among the representations made by the craftsman on the shield one can find a dancing team composed of two dancers who also perform gymnastic exercises: “And a great company stood around the lovely dance taking joy in it; and two tumblerswhirled up and down among them, leading the dance” [33]. Similarly, in Rhapsody 4 of the Odyssey, where Telemachus in seek of information about his wandering father is being hosted in Menelaus’ palace, a dance and music-gymnastic team offers a spectacle to the palace people and their guest. The special characteristics of that team are similar with those reported in the Iliad’s Rhapsody 18, with the addition of a minstrel singing to the lyre, “So they were feasting in the great high-roofed hall, the neighbors and kinsfolk of glorious Menelaus, and making merry; and among them a divine minstrel was singing to the lyre, and two tumblers whirled up and down through the midst of them, leading the dance” [34]. Also, in Odyssey’s Rhapsody 8, in Alcinous palace where Odysseus is being hosted, a group activity of two famous dancers and acrobats who simultaneously play with the ball, is more precisely described: “Then Alcinous made Halius and Laodamas dance alone, for no one could vie with them. And when they had taken in their hands the beautiful ball of purple, which wise Polybus had made them, the one would lean backward and toss it toward the shadowy clouds, and the other would leap up from the earth and skillfully catch it before his feet touched the ground again. But when they had tried their skill in tossing the ball straight up, the two fell dancing on the bounteous earth, constantly tossing the ball to and fro, and the other youths stood in the place of contests and beat time, and loud was the applause that arose” [35].

In the last two references, it can be observed that almost the same group activity is described in two different regions (Menelaus’ palace in Sparta, and Alcinous’ palace in the island of the Phaiakon). In Menelaus’ palace the activity includes three elements, “singing to the lyre…two tumblers…leading the dance” [36]. However, an element which stands out and is absolutely common in the two different references is the two tumblers' team. In the reference to Alcinous, a more complete description is given and the characteristic of interdependence towards the aim’s achievement is brought to light, since, in order to produce the spectacle, one should toss the ball up and the other should catch it while airborne. Moreover, the fact that Alcinous called specifically for his two sons Halius and Laodamas (as the best ones) in order to honor the foreigner, reveals the characteristic of recognition by a third person and the fact that they were members of the same team, established in Phaiakon’s society and possibly in the whole ancient Greece. That characteristic feature in conjunction with the co-ordination of the two tumblers signifies a preceding, long-lasting engagement with that matter, and indicates that naturally an intense interaction should have existed between them. It is therefore a small team of long duration that could be characterized as permanent.

Furthermore in the Odyssey’s Rhapsody 8, the dance and music part of the celebrating event commences in line 260, where Alcinous calls for the famous singer Demodocus to play the guitar, while groups of young people form around him and start dancing, before Halius and Laodamas are called for: “And around him stood boys in the first bloom of youth, well skilled in the dance, and they struck the sacred dancing floor with their feet” [37]. Those groups are reported in the wide sense of the term team, with no information regarding their number or the number of each team’s members. Surely, it is justifiable, as because of the limited space not many members could have positioned themselves around a singer. Those groups are interpreted as informal and occasional and do not seem to possess any dynamics, like the one of the famous Halius and Laodamas. However, it should be noted that a comparison of the two famous dancers with the others and their distinction possibly suggests the existence of more famous duets, being engaged in dancing events in conjunction with ball games. Furthermore, the fact that Polybus is being referred to as an experienced ball constructor, pertains to the fact that he had constructed other balls as well, in order to satisfy the needs of other dancing groups.

Moreover, in the Shield of Heracles, Hesiod describes the deathless gods’ dance at Olympus, to the accompaniment of Apollo’s lyre, where gods and nymphs were dancing; “And there was the holy company of the deathless gods, and in the midst the son of Zeus and Leto played sweetly on a golden lyre…” [38]. The Muses’ singing group is then mentioned: “Also the goddesses, the Muses of Pieria began a song like clear-voiced singers” [39]. The Muses’ team is cited in many places throughout the examined works, in regard to their common origin. Since Zeus was their father, they belong to the primary groups [40].

Dancing teams of young men and women to the accompaniment of flute, as well as equestrian teams, are depicted by Hesiod in the Shield of Heracles, but these teams are presented in the broad meaning of the term [41]. The classifications of certain activities take place in a city, which the poet imagines to be in a period of peace, and whose product are cultural teams.

Dancing and equestrian teams are mentioned in the Homeric Hymn “To Delian Apollo”, where in honour of Apollo in Delos, the Ions and their children were gathered, and dancing and fighting games were organized, “…mindful, they delight you with boxing and dancing and song, so often as they hold their gathering” [42].Those teams are defined in the wide sense of the term, except for the Daughters of Delos, who, like the Muses, were a composed team that praised the gods and could have been integrated in the category of small groups with high interaction among group members.

Also, in the Hymn to Pythian Apollo the gods’ dance is cited, in which groups of gods and various deities form a dancing team to the musical accompaniment of Apollo’s lute and under supervision of his mother Leto and Zeus. “Meanwhile the rich-dressed Graces and cheerful Seasons dance with Harmonia and Hebe and Aphrodite, daughter of Zeus, holding each other by the wrist” [43]. Three divine groups can be distinguished: the Graces verified in the Orphic Hymns and numbered to three [44]; the Hours that are mentioned by their names and number, like in the Orphic Hymns [45]; and also Aphrodites, representing the gods of Olympus.

For a long time ago, people have formed hunting groups of a few or more members. Those groups were created with the aim to find food, eliminate a dangerous beast or entertain the hunters. In the Iliad, hunting of dear and wild goat is mentioned in the reference to the panicking Trojans who were retrieving in some phase of the battle, like hunted animals, “But as dogs and country people pursue a horned stag or a wild goat,…” [46]. In those verses no special characteristics can be observed which might reveal the existence of a team in the strict sense of the term. The composition of hunting groups is only certified if their goal is hunting either for food or for sport. In the Odyssey, a hunting group and its famous members are mentioned while hunting a wild boar, “…that the beaters reached a certain wooded hollow. Ahead of them ran the hounds, hot on a scent. Behind came Autolycus’ sons, and with them the good Odysseus, close up on the pack and brandishing his long spear” [47].Autolycus and Odysseus are famous hunters and constitute a small team. There may also have been other members of the team who would have escorted the king’s children. Here, the common goal can be demonstrated, which is the hunt for the wild boar, and also the feature of recognition by others, expressed by the maid’s recognition of Odysseus at the sight of his wound from a wild boar and her reference to that particular group.

In the Shield of Heracles Hesiod describes a rabbit hunt by groups composed of a few members “...and huntsmen chasing swift hares with a leash sharp…” [48].In those verses, other group characteristics are not cited, but it should be pointed out that their description was made in the context of a castled state, in which other types of groups were also described, like dancing groups, sport groups, work groups, rural groups and others that the poet was envisaging in a peaceful state [49].

Considering the notion that beyond the narrow context of sport, dancing and hunting teams, characteristics of a group are similar, independently of its aim of creation and composition, this study has also included the investigation of various characteristics of other groups.

One category is divine groups, which are generally classified as natural groups, because their members descend from the same parent. Divine groups are observed in Homer’s both works, though mostly in the Iliad, with the dominant group of gods, while others groups are cited as well, like the group of Muses, Graces, Eileithyiaes, Hours, Nireides, etc. In the Iliad, the gods of Olympus, despite the common origin, which classifies them as a primary group, participate directly or indirectly in the Trojan War. Therefore the poet, who expresses the common perception of his era, describes the actions, emotions or judgements among members about themselves and others, which refer to characteristic features similar to the ones mentioned earlier in the text. In the following verse, the goddess Hera, who wants to strengthen her position in the group of gods, is trying to influence Zeus by addressing these words to him: “for truly you are far the mightier. Still my labor too must not be made οf no effect; for I also am a god, and my birth is from the same stock as yours, and crooked-counseling Cronos begot me as the most honored οf his daughters, doubly so, since I am eldest and am called your wife, while you are king among all the immortals” [50].Hera recognizes Zeus’ superiority and reminds him that they descend from the same parent. It is characteristic that she identifies herself as belonging to the group of gods, while there is also the characteristic of her role as Zeus’ wife, as well as being part ofhierarchy, since she is self-determining her ranking among gods just below Zeus. In the Iliad’s Rhapsody 1, the gods’ team activity is being demonstrated with Zeus at the head of them: “Now when the twelfth dawn after this had come, then to Olympus came the gods who are forever, all in one company, and Zeus led the way” [51]. The members’ common place of living is also demonstrated, and that is Olympus. The respect of all the members of the Olympian team is denoted in the Iliad’s Rhapsody 1, “All the gods together rose from their seats in deference to their father; nor did any dare to remain seated at his coming, but they all rose up to greet him. So he sat down on his throne;” [52]. The members’ respect towards the team’s natural leader indicates the leader–members interaction. Reference to the gathered members of the Olympian gods is also made in the Iliad’s Rhapsody 15: “and she came to steep Olympus, and found the immortal gods gathered together in the house of Zeus” [53], as well as in Rhapsody 20, “thus theyweregathered inside the house of Zeus” [54], and 24: “and they found the son of Cronos, whose voice resounds afar, and around him sat together all the other blessed gods who are for ever” [55]. Furthermore, in the Iliad’s Rhapsody 15, Poseidon while speaking to goddess Iris recalls that together with his brother gods Zeus and Hades they are offspring of the same father (Cronos) and mother (Rhea). He also states that he is aware of his power and roles, and that he, Zeus, and Hades constitute a special three-member group among gods. Being doubtful of Zeus’ total leadership, he only recognizes him as leader in the sky and considers him to be equal with him. “For three brothers are we, begotten by Cronos, and born of Rhea – Zeus, and myself, and the third is Hades, who is lord of the dead below. And in three ways have all things been divided, and to each has been apportioned his own domain. I indeed, when the lots were shaken, won the gray sea to be my home for ever” [56].

In Rhapsody 2 of the Iliad, the poet is referring to the Muses’ group, where their common descent and special role is demonstrated, which is the praise of the heroes’ and gods’ deeds. Their common place of living is also mentioned, which in combination with their common work, reveals an intense interaction developed among team’s members: “The Muses of Olympus, daughters of Zeus who bears the aegis, call to my mind all those who came beneath Ilios” [57].

Also, in Rhapsody 24 of the Odyssey, the poet refers to the Muses’ group by number nine, and their musical role is verified, “the Nine Muses chanted your dirge in sweet antiphony” [58], and shows a team with a small number of members that, apart from their common origin, suggests an intense interaction among them. Hesiod calls them Heliconiades, for they live on the mountain Helicon, and recognizes in them the same characteristics like Homer, including their permanence as a team. “From the Heliconian Muses let us begin to sing, who hold the great and holy mount of Helicon, and dance on soft feet about the deep-blue spring and the altar of the almighty son of Cronos” [59]. In other verses he also refers to them by their names, “these things, then, the Muses sang who dwell on Olympus, nine daughters begotten by great Zeus, Cleio and Euterpe, Thaleia, Melpomene and Terpsichore, and Erato and Polymnia and Urania and Calliope” [60]. Hesiod in Works and Days, calls the Muses’ group Pierides because they live on Olympus, located in Pieria’s county: “Muses of Pieria who give glory through song, come hither, tell of Zeus your father and chant his praise” [61]. It is the same team that is named after the region of its location [62]. In the Orphic Hymns, the Muses are also defined as Pierian and are cited by their names, like in Hesiod [63].

In Homer’s Iliad [64] and Odyssey [65], a group of deities with the name Horae is cited. Hesiod calls them by the names of Eurinome, Justice and Peace [66; 67]. The same group is praised in the 43rd Orphic Hymn to the Horae [68]. It is a group of three eminent deities aiming at the preservation of nature’s order and regular climate changes per season, with whom the growth and the fertility of the plants are occurring.

Moreover, being a cohesive group, with the common origin and aim, the three-member team of the mythological giants could be classified as a special divine category defined by Zeus as a warders' team. “There Gyes and Cottus and great-souled Obriareus live, trusty warders of Zeus who hold aegis” [69]. Due to Achilles’ injury, Homer refers to a group of Eileithyiae, who are deities with the special assignment to provoke pain warning for labour. This is a primary group, a natural one whose members descent from the common mother Hera, “…the piercing dart that the Eileithyiae, goddesses of childbirth, send – the daughters of Hera who have bitter pangs in their keeping – so sharp pains came on the mighty son of Atreus” [70].

Groups of deities are mainly cited in the Orphic Hymnsand partially in Hesiod’s Theogony. They are all characterized by being primary groups. They have the same parent and common purposerecognized by third people, and they are also aware that they belong to the same group.In Hymn 21, the group of Nephon that aims at the creation of rain is mentioned [71]. In Hymn 24 there are the Nereides, a group of sea nymphs [72]. The group of Koureites, composed of two brothers that are priests, is cited in Hymn 31 [73]. The Titans, the gods who reigned before the Olympian gods, are described in Hymn 37 [74]. In Hymn 51 are the Nymphs who were friends of play (philopaigmonaes) [75]; in 59 the Fates, a group of three eminent deities [76]; in 60 the Graces, named Aglaea, Thaleia, and Euphrosyne [77]; in 69 the Herinyes, Tisiphore, Allekto and Megaira [78]; in 70 the Eumenides that protected those in need of protection [79]; and finally in Hymn 81 the Auras or Zephyretedes [80].

Primary groups of mortals descending from the same parent are cited in the Iliad’s 12 Rhapsody and include Teucer and Telamonian Aias: “So saying Telamonian Aias went away, and with him went Teucer, his own brother, son of the same father, and with them Pandion carried the curved bow of Teucer” [81]. With the addition of Pandion, the group becomes a three-member war team. In the Iliad, the sons of Priam, the Atrides and others are also mentioned. Nestor’s suggestion to Agamemnon marks an awareness of the special unity and solidarity that can be developed in groups composed of relatives, or in those united by bonds of blood or by common descent, “separate the men by tribes, by clans, Agamemnon, so that clan may aid clan and tribe tribe” [82].

Also, the Iliad includes numerous military teams, which is natural, because, due to Achilles’ rage, the poet describes battles and military deeds of his heroes during the tenth year of the Trojan War. In particular, a large number of two-member chariot crews are described. It is known that the chariot was used in organized face-to-face battles, while it also served a transportation purpose. A characteristic example is the description of Achilles’ chariot crew, “and Automedon and Alcinous set about busily to yoke the horses,...And Automedon grasped in his hand the bright whip that fitted it well, and leapt on the chariot; and behind him stepped Achilles armed for battle” [83].

In those verses, the three-member chariot crew and the interdependent roles can be distinguished. While Achilles is fighting with his weapons, Automedon is the charioteer and together with Alcinous are preparing the chariot. In many other refe-rences, the number of the chariot crew members is two. This is characteristic of a small group, where its members display interdependent roles. Also, the long nine-year duration of the war leads to a conclusion that this is a lasting team, a fact that presupposes interaction between team members, which develops a dynamic situation on the battlefield. The poet recognizes that famous members belong to that team, which is shown by the feature of recognition by third people. A two-member team is formed by Priam and his charioteer, “and by his side Antenor mounted the beautiful chariot” [84]. It is probable that Priam, as a king, used all the time the same charioteer, Antenor, for transportation and, although the team seems to be formed in the wide sense of the term group, it could have been a permanent one. Military chariot teams with a lasting existence are mentioned in many places in the Iliad. In Rhapsody 5, a two-member team of Trojan warriors attacks Diomedes during the battle: “Now there was among the Trojans one Dares,…and he had two sons, Phegeus and Idaeus,…against Diomedes, they in their chariot” [85]. The lasting existence of the team reveals the intense interaction between its members. In the same rhapsody, chariot teams in the wide sense of the term can be observed among gods; “and she mounted on the chariot, her heart distraught, and beside her mounted Iris and took the reins in her hands. She touched the horses with the whip to start them” [86], as well as the team of Hera and Athena that was temporarily formed [87]. Also, in the Iliad’s Rhapsody 5, a mixed team of the mortal Diomedes and the goddess Athena is described, “And she stepped into the chariot beside noble Diomedes, a goddess eager for battle” [88]. There are also the chariot crews of the Trojans Mydon and Tilaimenis [89] and Axilus’ team with his charioteer Calesius [90]. In the Iliad’s Rhapsody 8, Hector's military chariot crew including his murdered charioteer Archeptolemus is cited [91]. Furthermore, in Rhapsody 11, where battles are described, three more references to military chariot crews can be distinguished. In the first one, a plethora of chariot teams and co-operation between the warrior and the charioteer are noticed: “Then on his own charioteer each man laid the charge to hold in his horses all in good order there at the trench, but they themselves on foot, arrayed in their armor, rushed swiftly forward, and a cry unquenchable rose up before the face of Dawn. In advance of the charioteers were they arrayed at the trench, but after them a little followed the charioteers” [92]. In the second reference, Agamemnon meets Priam’s famous sons who constitute a chariot team on the battlefield, “And made straight to slay Isus and Antiphus, two sons of Priam, one a bastard and one born in wedlock, the two being in one chariot: the bastard held the reins, but glorious Antiphus stood by his side to fight” [93], whom he later kills. The third reference is related to Agamemnon’s chariot, “Then he leapt on his chariot and commanded his charioteer to drive to the hollow ships” [94]. There is finally the fourth one about Diomedes’ two-member chariot crew, who leaves the battlefield injured, “Then he leapt on to his chariot and he charged his charioteer to drive to the hollow ships, for he was pained at heart” [95]. In Rhapsody 12, the Trojans are cooperating in battle with their charioteers, “then on his own charioteer each man laid the charge to hold back his horses all in good order there at the trench” [96].

In the Iliad’s Rhapsody 16, the chariot crew of Hector with his charioteer is also mentioned, “then to battle-minded Cebriones glorious Hector gave command to whip his horses into the battle” [97], while in Rhapsody 20, another famous Trojan chariot crew is quoted: “Then setting on Laogonus and Dardanus, two sons of Bias, he thrusts them both from their chariot to the ground” [98]. Reference to a chariot crew team is made by Hesiod in the Shield of Heracles, where the representations of Heracles and Iolaos, the charioteer, are described [99].

A representative example of a small group is the ship crew. Ship crews are nowadays regarded as small groups, whose special characteristic is frequent contact and members’ interaction. In the Homeric Hymn to Dionysus, pirates capture him, and without knowing he is a god, they put him on board, “When they saw him they made signs to one another and sprang out quickly, and seizing him straightway, put him on board their ship exultingly” [100]. In these verses, the pirates’ team purpose is demonstrated, which was the kidnapping of Dionysus, in order to ask for ransom and complete their mission. Then, their helmsman advises them to release him because he suspects Dionysus’ divine entity: “Then the helmsman understood all and cried out at once to his fellows and said…” [101]. The master’s intervention follows, who persists on kidnapping him criticizing the helmsman, “but the master chides him with taunting words: Madman, mark the wind and help hoist sail on the ship: catch all the sheets”[102]. From the last two references to the pirates’ team, which is simultaneously a ship crew, some roles that can be identified refer to hierarchy, leadership and members’ interaction. Ship crews are mentioned in all Homer’s works. Apparently, interaction among ship crew members is high and the team is a lasting one, since its members keep together for a long time.

In the Iliad, a ship crew of 20 [103] and 50 men is described, “in each ship…were fifty men, his comrades…pilots…stewards” [104], whereas in the Odyssey a ship crew of 20 men is present, “twenty rowers – men” [105]. In the Iliad’s Rhapsody 2, the leaders of the armies and the number of the ships that sailed to Troy are referred to by their names [106].

Many teams of military operations are also occasionally formed: “but the Cadmeians,...fifty youths and two there were as leaders, Maeon,...and Polyphontes, firm in the fight” [107]. Here the characteristic of the leader is shown, the number of team’s members (50), their common purpose being the killing of Tideus (cited in previous verses) and recognition by others, that those fifty persons belonged to that particular team along with their famous leaders. This is obviously a temporary team.

Furthermore, a withstanding example of a war team is the one of the Trojan Horse. The characteristic that can be identified is the common purpose of formation of the team and the awareness of its role, as well as of its leader, Odysseus; “…while those others led by glorious Odysseus were now sitting in the place of assembly of the Trojans, hidden in the horse;” [108]. This is a temporary team. A reference to another famous heroes’ team from the mythology is made by Hesiod. The team is composed of Heracles and Iolaos, whereas the goddess Athena who could have been added as well, supports them in all their accomplishments. “And her Heracles, the son of Zeus, of the house of Amphitryon, together with warlike Iolaus, destroyed with the unpitying sword through the plans of Athene the spoil-driver” [109].

The Olympian gods’ team with Zeus in the lead is also considered to be a decision making team, “now the gods, seated by the side of Zeus, were holding assembly” [110]. Also, under Nestor’s general command, the group of the elderly gathers for a meeting. During that meeting commenced by Agamemnon, Nestor speaks and encourages the leaders who are discouraged by the plague and deaths caused by god Apollo; “He spoke, and led the way out of the council, and the other sceptered kings rose up and obeyed the shepherd of men; and the troops were hurrying on” [111]. In those verses, the interaction feature can be identified, and the difference in the members psychological state before and after Nestor’s speech. There is also a description of a meeting of the leaders under Agamemnon’s general leadership, where members of those teams who made decisions, were famous and had a certain number of leaders, according to the poet’s description in the Iliad’s Rhapsody 2[112].

A rare type of social group is described in the Odyssey, which is constituted by the suitors hanging out in Odysseus’ palace who flirt with Penelope, having their eyes on the throne and entertaining themselves damaging the royal property. “But the suitors in front of the palace of Odysseus were making merry, throwing the discus and the javelin in a leveled place…; and Antinous and godlike Eurymachus were sitting there, the leaders of suitors” [113]. Telemachus, in seek of his father, speaks to the disguised goddess Athena and asks her about the identity of the gathered throng, located in and around his father’s palace, “what feast, what throng is this?”[114]. The group characteristic shown here is the common purpose which unites the members, pertaining to entertainment, welfare, and marriage with Penelope. The interaction among members seems to be high, because the suitors’ contact is frequent. Also, some suitors are referred to by their names, whereas in other verses, their number and origins are mentioned. “From Dulichium there are fifty-two, the pick of its young men, with six serving-men. From Same there are twenty-four, and from Zacynthus twenty noblemen; from Ithaca itself a dozen of its best, and with them Medon the herald, and an inspired minstrel, besides two servants, expert carvers” [115]. This reference offers the characteristic of recognition by others, since the suitors are all part of the same team.

Solidarity is a group characteristic that reinforces the group's dynamics. In the Iliad’s Rhapsody 3, the following verses demonstrate solidarity among the Achaeans: “but the Achaeans..., breathing fury eager at heart to come and assist each other” [116], whereas Rhapsody 15 reveals the element of being united at heart: “For shame held them and fear; for unceasingly they called aloud one to the other” [117]. In the following citation, the common purpose, which refers to defending to death of Patroclus, unites team members and reinforces cohesion. “But the Achaeans stood firm about the son of Menoetius with one purpose, fenced about with shields of bronze” [118]. The major component of cohesion is the perseverance to the cause [119]. Finally, many labour/rural teams are described by Hesiod as well [120].

The study of the texts from the epic period reveals in many verses a great number of actions or activities of crowds of people being in a situation of unity and group in the broad sense of the term, that can be psychologically interpreted by the crowd theory [121]. Because the study of the verses was originally conducted in ancient Greek with the aid of valid translations by distinguished scholars of Papyrus Publications [122]andLiddell & Skott reliable dictionaries [123], it was ascertained that in those phrases describing unitary actions, activities or situations, derivatives of the adjective omos, omi, omon meaning the same and constituting the root of the word team/group are included in various forms. “It was his two sons that lord Agamemnon took, the two being in one chariot, and together(omou)they were seeking to contain the swift horses”[124]. It can be observed that, although the two-member chariot crew constitutes a small group with intense interaction between its members, the poet places emphasis on the common effort with the adjective or adverb omou = together, which is to control the swift horses. The same grammatical form is found in Hesiod’s works. Also, the derivative noun omados = throng is used to denote team effort: “But they who were with the son of Atreus gathered in a throng, and the noise and din of their coming roused him” [125].

A remarkable approach towards the sense of the notion of group using the noun throng is adopted in the Iliad’s Rhapsody 7, in its accusative form in the meaning of a group of spectators of a common spectacle. The poet describes the throng of Trojan soldiers who are watching Hector’s duel with Aianta shouting and making noises, to whom Hector returns after the duel, whereas Aias comes back to the Achaeans respectively. “So they parted, and one went to the army of the Achaeans, and the other went to the throng of the Trojans” [126]. Group’s characteristics here are the same ethnicity (Trojans, Greeks), gathering in the same place, simultaneous shouting of the Trojans, common purpose – viewing of the duel, and support of their representatives in that duel. The psychology of the group is that of the crowd. It refers to large groups without a common contact among its members. This is a temporary team, since it is formed only for viewing the duel and is composed of existing opponent soldiers. The same grammatical form (omadon = tumult) is used by Hesiod to describe the opponent soldiers depicted in the shield of Heracles, built by Hephaestus; “They would cast that one behind them, and rush back again into the tumult and the fray” [127]. In the Iliad’s Rhapsody 19, the noun omados in its dative form omado = the uproar of many, expresses a team situation: “And among the uproar of many how should a man either hear or speak?” [128].

Also, the composite noun omilos (group), whose first composite is omos and the second is ili meaning cavalry, is metaphorically used for the ascription of various groups of numerous members (omos+ili = omilos = throng). In the Iliad’s Rhapsody 3, Alexander returns to the Trojans’ throng, “so did godlike Alexander, seized with fear of Atreus’ son, shrink back into the throng of the lordly Trojans” [129]. In Rhapsody 19, omilos is used in the verb form omilisosi, “when once the ranks of men meet” [130]. In the Odyssey, the noun omilos applies to the suitors flirting with Penelope. The poet refers to them as the suitors’ throng [131]. The Homeric Epics and Hesiod’s works include many similar grammatical forms, denoting opponent warriors illustrated in the hero’s shield.

In the contemporary Greek language, to indicate the notion of team the noun omas – omados (group) is used, from which according to Kontos [132], after the Homeric and Byzantine periods the form omada – omadas (group) [133]and sport team was formed. Many Greek scholars from the Hellenistic to the modern years assert that the word omas and omada are derivatives of the adjective omos-omi-omon meaning the one and only, he/she/it, the same or alike, the common, the united. In Latin, it is expressed in the form communis [132, 133]. It is possible that omos derives from the adverb ama meaning right away, simultaneously and it is mainly used as a temporary adverb. Adamantios Korais asserts that the word omos may derive from the adverb from the Dorian dialect oma, and is similar to the dative form of the noun oma [134]. Kallimachus[135] also used the form kath’oma, which in Hesychious dictionary is recorded in the form kathomon meaning the same as (kath’omoion) [136]. Souidas interprets kathomon as unity and friendship[137]. During the Byzantine years, the adverb omadon was formed which derives from the noun omada and means omadika i.e. all together, all at the same time.

It can be concluded that a definition of group or team is not to be found in the works of the epic cycle. However, many activities from two or more persons were observed, in which some characteristics that establish various types of groups were identified. These characteristics are the common purpose, recognition by others, consciousness of belonging to the group, interdependent roles, interaction among members, leadership, solidarity, unity and cohesion. The sport teams described are chariot crews, or playing teams with or without the ball in conjunction with gymnastic exercises. In the Odyssey there are mostly, music and dancing teams, entertainment teams combined with acrobatics, and hunting teams. Despite a few references to sport teams in the Iliad, war groups and teams of military operations are denoted, resulting naturally from the Trojan War operations, whereas groups of gods and deities were cited in many other places as well.

[1] Liddell, H.G., Skott, A., Summary table of the periods of Greek Grammatology. Great Dictionary of the Greek Language, I. Sideris Publications, Athens 1948, p. 1.

[2] Thucydides, Histories, G, 104.

[3] Hasapis, C., Greek astronomy in the second millennium BC according to the Orphic Hymns, Doctoral Dissertation 1967, D.P. Papaditsas & E. Ladia, Orphic Hymns, Imago Publications, Athens 1984, p. 8.

[4] Homer, Iliad, 23.

[5] Homer, Iliad, 6.

[6] Adorno, T., Horkaimer M., Institut für Sozialforschung Soziologische Exkurse 1956, Kritiki Publications, Athens 1987, p. 75.

[7] Zimmel, G., Soziologie, 2nd Ed., Muenchen, Lipsia 1922.

[8] Oppenheimer, F., System der Soziologie, vol. 1, no. 2, 1923, (in:) T. Adorno, M. Hor-chaimer, Institut für Sozialforschung Soziologische Exkurse 1956, Kritiki Publications, Athens 1987, p. 462.

[8] McDougall, W., The Group Mind, Cambridge University Press, London 1921, p. 66.

[10] Geiger, T., Sociologie, Kopeghagen 1939, p. 36.

[11] Bogardus, E.S., Sociologei, New York 1940, p. 4.

[12] Weise, L., System der Allgemeinen Soziologie, Muenchen, Lipsia 1933.

[13] Homans, G., The Human Group, New York 1950, p. 2.

[14] Cooley, C. H., Human Nature and the Social Order, Scribner, New York 1902.

[15] Vierkandt, A., Kleine Gesellschaftslehre, Stoutgardi 1949.

[16] Adorno, T., Horkaimer, M., Institut fur Sozialforschung Soziologische Exkurse, 1956, Kritiki Publications, Athens 1987, p. 84.

[17] Lewin, K., The field theory, Harper & Row Publishers, New York 1948, p. 84.

[18] Festinger, L., Schachter, S., Back, K., Social pressures in informal groups, Stamford University Press 1950, p. 58.

[19] Cartwright, D., Zander, A., Groups and Group Membership, (in:) D. Cartwright, A. Zander, eds., Group Dynamics: Research and theory, Harper & Row Publishers, New York 1968, pp. 45-62.

[20] Johnson, D.W., Johnson, F.P., Group theory and group skills, 3rd Ed., NJ: Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs 1987, p. 8.

[21] Bales, R., Interaction process analysis, Addison-Wesley Press, Cambridge, Mass 1950, p. 46.

[22] Show, M.E., Group Dynamics, 3rd Ed., McGraw-Hill, New York 1978, p. 8.

[23] Fiedler, F.E., A theory of leadership effectiveness, McGraw-Hill, New York 1967.

[24] Carron, A.V., Social psychology of sport, Movement Publications, Ithaca, New York 1980.

[25] Cartwright, D., Zander, A., Groups and Group Membership (in:) D. Cartwright, A. Zander, eds., Group Dynamics: Research and theory, Harper & Row Publishers, New York 1968, pp. 45-62.

[26] Homer, Iliad, 23, 641-642.

Bales, R., Interaction process analysis, Addison-Wesley Press, Cambridge, Mass 1950.

[28] Homer, Odyssey, 6, 99-116.

[29] Homer, Odyssey, 7, 290-291.

[30] The Homeric Hymns, To Demeter, 417-425.

[31] Lott, A.J., Lott, B.E., Group cohesiveness as interpersonal attraction: A review of relationships with antecedents and consequent variables, “Psychological Bulletin”, 64, 1965, pp. 259-309.

[32] Lott, A.J., Lott, B.E., Group cohesiveness as interpersonal attraction: A review of relationships with antecedents and consequent variables “Psychological Bulletin”, 64, 1965, pp. 259-309.

[33] Homer, Iliad, 18, 604-605.

[34] Homer, Odyssey, 4, 15-19.

[35] Homer, Odyssey, 8, 370-379.

[36] Homer, Odyssey, 4, 15-19.

[37] Homer, Odyssey, 8, 262-264.

[38] Hesiod, Shield of Heracles, 201-202.

[39] Hesiod, Shield of Heracles, 204-206.

[40] Cooley, C.H., Human Nature and the Social Order, Scribner, New York 1902.

[41] Hesiod, Shield of Heracles, 278-324.

[42] The Homeric Hymns, To Delian Apollo, 149-164.

[43] The Homeric Hymns, To Pythian Apollo.

[44] The Orphic Hymns, 60, The Graces.

[45] The Orphic Hymns, The Hours.

[46] Homer, Iliad, 15, 271-272.

[47] Homer, Odyssey, 19, 435-439.

[48] Hesiod, Shield of Heracles, 301-302.

[49] Hesiod, Shield of Heracles, 270-325.

[50] Homer, Ιliad, 4, 56-61.

[51] Homer, Iliad, 1, 493-495.

[52] Homer, Iliad, 1, 533-536.

[53] Homer, Iliad, 15, 83-85.

[54] Homer, Iliad, 20, 10-13.

[55] Homer, Iliad, 24, 62-63.

[56] Homer, Iliad, 15, 187-199.

[57] Homer, Iliad, 2, 488-492.

[58] Homer, Odyssey, 24, 60-61.

[59] Hesiod, Theogony, 1-4.

[60] Hesiod, Theogony, 74-79.

[61] Hesiod, Works and Days, 1-2.

[62] Lekatsa, P., Introduction to Hesiod, Works and Days, vol. VI, Papyrus, Athens 1975.

[63] The Orphic Hymns, The Muses, 76.

[64] Homer, Iliad, 5, 749.

[65] Homer, Odyssey, 24, 344.

[66] Hesiod, Theogony, 58-62.

[67] Hesiod, Theogony, 901.

[68] The Orphic Hymns, The Horae, 43.

[69] Hesiod, Theogony, 735.

[70] Homer, Iliad, 11, 269-272.

[71] The Orphic Hymns, 21, The Nephi.

[72] The Orphic Hymns, 24, The Nereides.

[73] The Orphic Hymns, 31, The Koureites.

[74] The Orphic Hymns, 37, The Titans.

[75] The Orphic Hymns, 51, The Nymphs.

[76] The Orphic Hymns, 59, The Fates.

[77] The Orphic Hymns, 60, The Graces.

[78] The Orphic Hymns, 69, The Herinyes.

[79] The Orphic Hymns, 70, The Eumenides.

[80] The Orphic Hymns, 81, The Zephyretedes.

[81] Homer, Iliad, 12, 370-372.

[82] Homer, Iliad, 2, 362-363.

[83] Homer, Iliad, 19, 392-399.

[84] Homer, Iliad, 3, 310-313.

[85] Homer, Iliad, 5, 9-13.

[86] Homer, Iliad, 5, 364-372.

[87] Homer, Iliad, 5, 745-749.

[88] Homer, Iliad, 5, 837-839.

[89] Homer, Iliad, 5, 580-583.

[90] Homer, Iliad, 6, 17-19.

[91] Homer, Iliad, 8, 312-313.

[92] Homer, Iliad, 11, 47-52.

[93] Homer, Iliad, 11, 101-104.

[94] Homer, Iliad, 11, 273-275.

[95] Homer, Iliad, 11, 396-400.

[96] Homer, Iliad, 12, 81-87.

[97] Homer, Iliad, 16, 726-739.

[98] Homer, Iliad, 20, 460-462.

[99] Hesiod Shield of Heracles, 118-127.

[100] The Homeric Hymns, To Dionysus, 8-10.

[101] The Homeric Hymns, To Dionysus, 15-16.

[102] The Homeric Hymns, To Dionysus, 25-27.

[103] Homer, Iliad, 16, 168-172.

[104] Homer, Iliad, 8, 42-44.

[105] Homer, Odyssey, 4, 669.

[106] Homer, Iliad, 2.

[107] Homer, Iliad, 4, 391-395.

[108] Homer, Odyssey, 8, 502-503.

[109] Hesiod, Theogony, 317-318.

[110] Homer, Iliad, 4, 1-2.

[111] Homer, Iliad, 2, 86-88.

[112] Homer, Iliad, 2.

[113] Homer, Odyssey, 4, 625-629.

[114] Homer, Odyssey, 1, 225.

[115] Homer, Odyssey, 16, 247-253.

[116] Homer, Iliad, 3, 1-9.

[117] Homer, Iliad, 15, 658-659.

[118] Homer, Iliad, 17, 266-268.

[119] Mullen, B., Copper, C., The relation between group cohesiveness and performance: An integration, “Psychological Bulletin”, 1994, 115, pp. 210-227.

[120] Hesiod, Shield of Heracles, 281-324.

[121] Le Bon, Psychologie des foules, Presses Universitaires de France, Quadrige 1991.

[122] Papyrus Publications, Athens 1975.

[123] Liddell, H.G., Skott, A., s.v. omos, omou, oma, omose, omados, omadeuo, Great Dictionary of the Greek Language, I. Sideris Publications, Athens 1948.

[124] Homer, Iliad, 11, 126-127.

[125] Homer, Iliad, 23, 233-234.

[126] Homer, Iliad, 7, 306-307.

[127] Hesiod, Shield of Heracles, 257.

[128] Homer, Iliad, 19, 81-82.

[129] Homer, Iliad, 3, 36-37.

[130] Homer, Iliad, 19, 158.

[131] Homer, Odyssey, 1, 225.

[132] Kontos, K., Literary varieties, Vol. 1, Perri Brothers Printing Office Athens, 1889. pp. 151-186. K. Kontos (1834-1909), a distinguished Greek scholar, leader of the only literary school in Greece, Professor of Greek language in Athens University, student and co-worker of Gabriel Gobbet in Ladle, Holland.

[133] Liddell, H.G., Skott, A., Great Dictionary of the Greek Language, I. Sideris Publications, Athens 1948, p. 124.

[134] Adamantios Korais (1748-1883), (in:) K. Kontos, Literary varieties, Vol. 1, Perri Brothers Printing Office, Athens 1889, p. 158. A distinguished Greek scholar, and a great teacher of the Greek Genus, the fundamental representative of the Neohellenistic Illuminism.

[135] Kallimachus, (in:) K. Kontos, Literary varieties, Vol. 1, Perri Brothers Printing Office, Athens 1889, pp. 151-186.

[136] Hesychius, (in:) K. Kontos, Literary varieties, Vol. 1, Perri Brothers Printing Office, Athens 1889, pp. 151-186.

[137] Souidas, (in:) K. Kontos, Literary varieties, Vol. 1, Perri Brothers Printing Office, Athens 1889, pp. 151-186.

KATERINA MOURATIDOU, ATHANASIOS ANASTASIOU,

ATHINA MOURATIDOU, IOANNIS MOURATIDIS

Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Correspondence should be addressed to: Katerina Mouratidou, T.E.F.A.A. Serron, 62110

Ag. Ioannis, Serres, Greece.

Key words: Dance; Ancient Greece; Dance Categories; Educational Dance.

The approach of ancient Greeks to dance differed radically from the one which dominates today. The concept of dance was used in ancient Greece to convey not only rhythmical human actions but also movements of all living beings in nature. However, a single term was insufficient to describe such a multidimensional phenomenon. This was possibly the reason behind the existence of three verbs related to dance and dancing movements in the ancient Greek language: χορεύω, ορχέομαι, μέλπω. It is quite remarkable how the structural components of dance were harmonized – according to archaeological sources – into a unified organizational entity, where all dancing movements were grouped into: φορά, σχήματα, δείξις. Initially, dance had a religious character, which was developed through the ages into three discernible categories: religious dance, war dance, and cultural dance. During the geometrical era, and even more profoundly in the classical years, dance attained a particular educational value. The Athenian youth of high social classes enjoyed private lessons in dance, music, and poetry by famous dancing-masters (the so-called ορχηστοδιδασκάλους).

A great number of sources that the archaeological spade has brought into light refer to dance. These, together with written references of poets, historians and philosophers, are an irrefutable testimony of the central role of dance in cultural and religious life in ancient Greece. Especially significant is the information from Homeric works, as they include details related to singing and dancing, which all imply that dance was a crucial component of the Mycenaean civilization [1].

As indicated in the above sources, ancient Greeks’ idea about dance differed from the contemporary conception. References, like those of Euripides in “Ion” and “Bacchai” who presented the earth, the air, and the moon dancing [2], lead us to a conclusion that dance for the ancient Greeks was not just a human rhythmical activity, but it also included movements of all living beings.

This multidimensional character of dance may serve as an interpretive key for the existence of three verbs in the ancient Greek language referring to dancing: ορχέομαι (orcheomae) [3], μέλπω (melpo) [4] and χορεύω (chorevo) [5]. As early as in the 8th century BC, in Homeric epic poems, we can come across three terms derived from the above verbs that can be translated as dance: ορχηθμός (orchethmos) [6], μολπή (molpe) [7], and χορός (choros) [8].

It is difficult to make a definite distinction between these three meanings. However, researchers could be helped by the study of ancient scripts, in which a great number of references to these three terms were made.

The word χορός for Homer represents the venue of a dancing meeting [9], but also execution of the dance and joy of the participants [10]. Furthermore, Plato in his “Laws” supports that the word χορός comes from the word χαρά (chara – joy) [11]. For him, choir-training (χορεία) embraces both dancing and singing [12], and the actual performance is an imitation of different personal characteristics, exhibited in actions and circumstances of every kind, in which several performers act their parts by habit and imitative art [13]. The most recent research into this subject has been conducted by Toelle and Wegner. Wegner agrees with everything that has been written above [14], but Toelle claims that the word χορός refers to the root χειρ (hand), and consequently to the hand movements [15]. The word ορχηθμός, is the Homeric type of the word όρχησις (orchesis) and refers to a dance movement with special characteristics and mimicry elements [16]. An example of ορχηθμός from The Odyssey 8-370 to 380, serves a useful explanation: Halius and Laodamas (Alcinous’ sons) are in the king’s palace and they are performing a dance to Odysseus and Phaiakes [17]. The two artists are playing with a ball and jump high, while the young men around them applaud rhythmically. The main components here are the game, the two dancers, and the spectators. Musical accompaniment is not considered a necessary element of ορχηθμός, as there are lines in Homeric epic poems where ορχηθμός takes place without music [18]. In a few words it can be said, that ορχηθμός is not a cyclic dance – as χορός is – but it is a physical activity consisting of rhythmic movements, which can take place without a musical accompaniment [19].

Μολπή can be regarded as dancing and singing at the same time [20]. Accor-dingly, Wegner writes that, “Probably, μολπή means the same as μέλπομαι εν χορώ, that is singing during dancing, without music instruments” [21]. If one relates the word μολπή to the verb μέλπω, he/she can see that the above interpretation is correct. According to the Lidell-Scott lexicon the word μέλπω means “to celebrate with song and dance” [22]. In the case of μολπή a dance group is also a choir, which takes care of the musical part of the dance. This view was also supported by Pindar who wrote: “And the swelling strains of song shall answer to the pipe’s reed” [23].

Furthermore, it can be noted that in ancient Greece the constituent elements of dance were harmonized into a unique combination, in which all dancing movements could have been divided into σχήματα (schemata), φορά (fora), and δείξις (deiksis).

According to Plato, the word σχήματα is the basic definition for all kinds of gestures and body postures [24]. Euripides and Aristophanes use in their works the word σχήματα with the meaning of gambols [25]. The analysis of the word σχήματα brings us to the meaning of “form, shape and figure” [26]. In relation to dance, σχήματα are clear and temporary postures and mimic movements or gestures made during dance. Some σχήματα continue just for a few seconds, while others have a longer duration. Other σχήματα can be repeated continuously to make a greater impression on the spectators.

The words φέρω (fero) and φορά have the same root. The verb φέρω in ancient Greece could have been interpreted as “to bear, convey with collateral notion of motion” [27]. According to this interpretation the word φορά could have meant the way a dancer used to ‘transport’ or ‘convey’ his body from one position to another.

As for the word δείξις, it refers to the same root as the verb δείκνυμι (deiknymi). Δείκνυμι in some cases meant ‘bring into the light, show forth, prove, offer’ [28]. Therefore the word δείξις could have meant the dancer’s representation of a man, animal or mythical being [29]. In other words, a dancer could have expressed through his dance all the characteristics of the being, or any element he possessed. In this case the main role was attributed to the dancer’s gestures, therefore he could have been called χειρόσοφος (skilled with the hands, gesticulating well).

The distinction of dance components in φορά, δείξις and σχήματα leads us to a conclusion that dance in ancient Greece was not merely a combination of steps but also a highly developed art which included a variety of theatrical and symbolic elements. The art of dance could have been considered an expression of the power of human soul, and functioned as a messenger to the spectators. The evolution and multilateralness of dance was an emanation of the unbroken relation of dance to music and song. Rhythm was a common factor and the benchmark of this unity, which remained intact until the Hellenistic age, having retained the name ορχηστική τέχνη (orchestic art, meaning the art of dancing). Terpsichore was the personification of the orchestic art, because she was considered to be the Muse of dance and choir-chants. Orchestic art included all body movements that could have expressed something. Moreck claims that orchestic art “was a science of postures and movements that taught and adjusted the beautiful postures during the sacred dances” [30].

Initially, music, song and dance in the ancient Greek world were closely related to the Olympian Gods and to every religious ceremony. They honored the Gods with processions, prayers, dances, contests, and sacrifices [31]. Later on, dance was further developed and obtained more characteristics, so that it could be divided into three major categories: religious, war, and cultural dance.

Religious dance in ancient Greece was an integral part of the ceremonies. It facilitated the believers’ introduction to the sacred secrets, prepared both soul and body to communicate with Gods during the processions to temples, and cleared the participants of human passions. It was a slow and serious dance without arm movements, mostly executed around the Gods’ altars. Such dances included Caryatids’ dance, Paian, Labyrinth, Anthema, Prosodion, and Yporchema.

War dance was, along with religious dance, one of the oldest expressions of the art of dance in general. In ancient Greece it was performed during preparation for war or athletic training. The dancers were armed and by stomping and yelling became possessed by war mania. Dances of that sort were used by Achaean aristocrats but also by the common folk in the Homeric epic poems. Characteristic examples of war dance were Pyrriche [32], Gymnopaedic orchesis, and Marches.

Cultural dance could be divided into two subcategories: a) dances of private life, and b) dances in ancient Greek dramatic art. Private life dances accompanied the citizens in their daily life. They were dances of banquets, weddings, celebrations (e.g., Epilenios orchesis, Hormos), and funerals (e.g. Threnos). Furthermore, all dances performed during athletic and music competitions can also fit this category. For example, during the Panathenaea a characteristic dance competition with prizes was known to be taking place. During the Pythian Games, which were equal to the Olympic Games, also similar music competitions were held, which included dancing [33].

Dances in ancient Greek dramatic art [34] were a valuable component and could be divided into three subcategories (as the dramatic art itself): Emmeleia was a tragedy dance, Kordax – a comedy dance, and Sikkinis – a satiric drama dance. Emmeleia had a serious and festal character and could have been easily recognized by symbolic hand and leg movements. Kordax had a comic and rude character, with vulgar movements especially of the pelvic region. Finally, Sikkinis was a dance with many springs, quick rhythm, and body rotations.

In conclusion, dance was placed among the higher arts in ancient Greece. It had been a precious and inseparable part of the Greek civilization since the Homeric ages. Dancing performances were related to a broad variety of daily, religious and cultural practices. This proves without any doubt the significance of dance in ancient Greece and justifies its use in Greek educational institutions.

The educational value of dance had been recognized by ancient Greeks since the geometric period, and it was established by ancient writers such as Lucian, who wrote in his work “The Dance”:

“Then are you willing to leave off your abuse, my friend, and hear me say something about dancing and about its good points, showing that it brings not only pleasure but benefit to those who see it; how much culture and instructions it gives; how it imports harmony into the souls of its beholders, exercising them in what is fair to see, entertaining them with what is good to hear, and displaying to them beauty of soul and body? That it does all this with the aid of music and rhythm would not be a reason to blame, but rather to praise it” [35].

From the above it can be seen that the religious experience of dance was used during the geometric age as a way of education [36]. Greek philosophers themselves considered dance to be a vital element for the harmonic evolution of man, and applauded its role in their scripts. Socrates asserted that dance exercised the whole body and balanced everything, “not like the long-distance runners, who develop their legs at the expense of their shoulders, nor like the prize-fighters, who develop their shoulders but become thin legged” [37].

Music together with dance was also used in the ancient Greek world as a basic educational tool, because it contributed to the positive use of youth’s spare time and inner cultivation. It is obvious from the study of scripts that music and dance together with sacrifices and athletic games were at that time the most characteristic aspects of a civilized society [38]. In contrast, war frenzy was accurately described by ancient Greeks using the terms ‘άχορος’ and ‘ακίθαρις’ (foe to the dance and lute) [39].

An earlier philosophical reference to the combination of dance and music comes from Plato. His works “Republic” and “Laws” make it obvious that the education of the young is directly related to dance and ode [40]. For Plato, dance and music contribute effectively to people’s character configuration and integration. In his ideal world, society preserves dance and music as the main ways of educating the youth. Dance and music were used to shape young men’s character and to help them achieve free citizen’s consciousness [41]. It seems that the realization of a good citizen was possible through music, song and performance of particular dances. For the young the aim of the dancing art was to imitate the older citizens and try and be equal to them.

According to Aristotle, music “influence reaches also in a manner to the character and to the soul” [42]. Plato considers dance a God’s gift, and him who has not been trained in the chorus an uneducated and uncultivated person [43]. He points out that the knowledge of dance contributed to the harmonic movement of the body [44]. Harmony and rhythm in dance were the vehicles of the character, because they were imitations of movements characterized by specific virtues and sentimental situations [45]. Plato suggests that the best time to begin one’s body training be the 6th year of life, whereas Aristotle the 5th year. With regard to warrior training Plato asserted the following in his “Republic”:

“What, then, is our education? Or is it hard to find a better than which long time has discovered? Which is, I suppose, gymnastics for the body and music for the soul” [46].

During the Greek classical ages the ideal citizen was the so-called καλοκάγαθος (kalokagathos) – a human being cultivated equally spiritually and physically. “Kalos he was the pride and joy of Athens and agathos a virtuous and noble” [47]. For this purpose ancient Athenians utilized the orchestic art for the education of the young.

“In ancient Greece dance possessed, at least until the Hellenistic ages, the central role in the process of the education. The Greeks intended it an attainment of a physical and spiritual harmony, and placed dance as a harmonic development of the body and cultivation of aesthetic kinetic forms” [48].

According to Schwikowski, the dancing festivals were schools of good manners, while the images of dancers served as models of nobility and morality to the youth [49]. Thereby the Athenian youth of high social classes enjoyed private dance, as well as music and poetry lessons by famous teachers [the so-called ορχηστοδιδασκάλους (orchestodidaskalous) – dancing-masters].

Consequently, the educational properties of dance influenced all the city-states in ancient Greece. By common acceptance, dance became necessary for the evolution of the self, and prepared young men to fight. For example, the war dance Pyrrhiche was a very important part of martial training. As Klein mentions, “Dance with its physical training functioned also as a war preparation” [50]. In Sparta and Crete, girls of all social classes – regardless of the hierarchical structure of society – enjoyed dance lessons [51].